"No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man"

--Heraclitus, Ancient Greek Philosopher

The Khoisan, the first people to occupy the Southern tip of Africa called Cape Town,

CAMISSA - 'the place of sweet waters'.

This is the story of Cape Town as told through the Water.

CAMISSA - 'the place of sweet waters'.

This is the story of Cape Town as told through the Water.

|

GENRE:

DIRECTOR / PRODUCER: CONSULTANT / ASSOCIATE PRODUCER: FORMAT: |

FEATURE LENGTH DOCUMENTARY

MARK J. KAPLAN CARON VON ZEIL HIGH DEFINITION |

SYNOPSIS

OVERVIEW

Iconic Table Mountain, Cape Town.

Cape Town, nestling below Table Mountain, is one of the globe’s most iconic images. The rugged, flat top of the mountain contrasting with the soft table-cloth-cloud spilling over its edges, make it a living monument to the forces that shape it: wind and water.

Water is the key to understanding and appreciating the natural history of the Table Valley. The story of the water flowing off the mountain links the natural to the political and cultural landscapes of the city.

The streams that run from the mountain brought the Khoisan here every spring for up to 1500 years before colonial settlement. The springs and streams that flow through the dry summer (unusual along the African coast) were the key to farming the land. Water drove the wheels of industry and quenched the thirst of beasts, residents and passing sailors. Until well into the 1900s, the principal economic base was supplying passing ships, and water was central to making that feasible.

The unique stories surrounding the sweet waters that flow from a series of artesian springs beneath the iconic Table Mountain are a symbol of the many trials and tribulations that accompanied the displacement of first nation users, the disparity in society that arises when the privileged are given preferential access, and the subsequent abuse of a resource to the point of collapse. Water-related issues are a priority, not only because future economic growth relies on adequate provision of water that will sustain development for present and future generations – but life itself.

The film touches on the realities and possibilities of the calamity of climate change. And though the regional aspects of the role of water in structuring the cultural landscape are explored, these reflect global opportunities for humankind to review our natural world through new eyes and thus transform our current thinking from doom to hope.

Until the turn of the 20th century, water from the mountain sustained the population growth of the peninsula, till demand outran supply and it had to be brought from greater distances. The way streams were channeled down and across valleys, gave the form to land holdings and is the essence of the spatial geometry of Cape Town.

The story of Table Mountain’s water is the story of power. It is the story of forgotten voices, of people displaced, of slavery and of slavery overturned. It is the story of water being harnessed as well as being wasted. In fact, as we follow the water, back and forward in time, we uncover many interwoven stories and forgotten voices alternating between moments of technological ingenuity, as well as stupidity, of enlightenment, as well as barbarism. Throughout, there are the profound links between the past, the present and the future.

Today, Cape Town is water challenged: chronic shortage coupled with extreme water pollution. Restrictions on water usage are currently legislated. Tomorrow will bring the additional realities of climate change: rising sea levels and periods of alternating flooding and drought.

Water is the key to understanding and appreciating the natural history of the Table Valley. The story of the water flowing off the mountain links the natural to the political and cultural landscapes of the city.

The streams that run from the mountain brought the Khoisan here every spring for up to 1500 years before colonial settlement. The springs and streams that flow through the dry summer (unusual along the African coast) were the key to farming the land. Water drove the wheels of industry and quenched the thirst of beasts, residents and passing sailors. Until well into the 1900s, the principal economic base was supplying passing ships, and water was central to making that feasible.

The unique stories surrounding the sweet waters that flow from a series of artesian springs beneath the iconic Table Mountain are a symbol of the many trials and tribulations that accompanied the displacement of first nation users, the disparity in society that arises when the privileged are given preferential access, and the subsequent abuse of a resource to the point of collapse. Water-related issues are a priority, not only because future economic growth relies on adequate provision of water that will sustain development for present and future generations – but life itself.

The film touches on the realities and possibilities of the calamity of climate change. And though the regional aspects of the role of water in structuring the cultural landscape are explored, these reflect global opportunities for humankind to review our natural world through new eyes and thus transform our current thinking from doom to hope.

Until the turn of the 20th century, water from the mountain sustained the population growth of the peninsula, till demand outran supply and it had to be brought from greater distances. The way streams were channeled down and across valleys, gave the form to land holdings and is the essence of the spatial geometry of Cape Town.

The story of Table Mountain’s water is the story of power. It is the story of forgotten voices, of people displaced, of slavery and of slavery overturned. It is the story of water being harnessed as well as being wasted. In fact, as we follow the water, back and forward in time, we uncover many interwoven stories and forgotten voices alternating between moments of technological ingenuity, as well as stupidity, of enlightenment, as well as barbarism. Throughout, there are the profound links between the past, the present and the future.

Today, Cape Town is water challenged: chronic shortage coupled with extreme water pollution. Restrictions on water usage are currently legislated. Tomorrow will bring the additional realities of climate change: rising sea levels and periods of alternating flooding and drought.

INTENTION

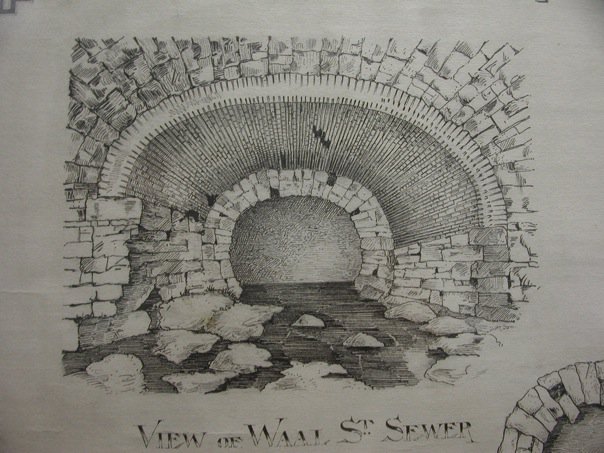

Cape Town's raison d'etre - lost beneath the streets

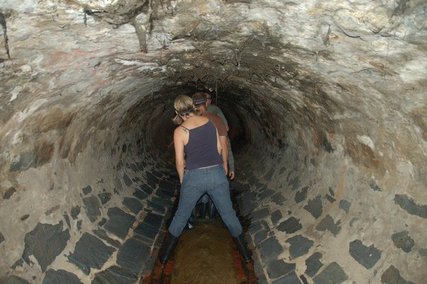

We are producing a feature length documentary aimed at a global audience. The film will be carefully scripted and multi-layered, but never “preachy”. Our journey along the river course is spiritual and uplifting as well as being surprising and informative. We will literally plumb the depths and follow the water as it moves underground via the man-made structures that direct the water under busy streets to reservoirs and ultimately to the sea. The water is not easily deflected and it continues to bubble up, sometimes in the most surprising of places, such as in the precinct of parliament.

There is a celebratory aspect to the film, characterized by the work of contemporary South African artists whose installations add to the film’s cultural edge. The waters flowing off Table Mountain have, since time immemorial, held locals in its spiritual sway. The Platteklip gorge remains a site of religious observances from many faiths. The rituals of the Khoisan are remembered as are those of the Slave Washerwomen.

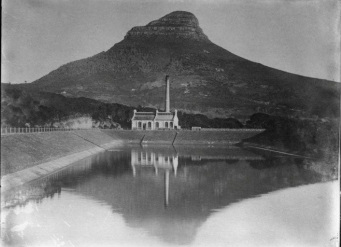

The waters of Table Mountain were both revered and defiled, at times the source of well-being but sometimes also a carrier of life-threatening diseases, such as the Smallpox epidemic of 1713 and the Bubonic plague. At different points along the water’s course mills were built and power was generated from the water’s flow. Relics of these mills still exist and the contestations around them still hold pertinent lessons today. Cape Town, a colonial backwater, an outpost of relative insignificance in the British Empire, utilised its water to generate electricity for its street lighting, while London still relied on gas lamps.

There is much to be learnt from the past as we confront the challenges of climate change, water shortages and rising sea levels. The stories of water are rich in texture, redolent with memories, myths and cultural practices. This is an opportunity to produce an evocative film which challenges the stereotypes, delights our senses and adds to our understanding of life as it has been lived on the southern tip of the African continent.

There is a celebratory aspect to the film, characterized by the work of contemporary South African artists whose installations add to the film’s cultural edge. The waters flowing off Table Mountain have, since time immemorial, held locals in its spiritual sway. The Platteklip gorge remains a site of religious observances from many faiths. The rituals of the Khoisan are remembered as are those of the Slave Washerwomen.

The waters of Table Mountain were both revered and defiled, at times the source of well-being but sometimes also a carrier of life-threatening diseases, such as the Smallpox epidemic of 1713 and the Bubonic plague. At different points along the water’s course mills were built and power was generated from the water’s flow. Relics of these mills still exist and the contestations around them still hold pertinent lessons today. Cape Town, a colonial backwater, an outpost of relative insignificance in the British Empire, utilised its water to generate electricity for its street lighting, while London still relied on gas lamps.

There is much to be learnt from the past as we confront the challenges of climate change, water shortages and rising sea levels. The stories of water are rich in texture, redolent with memories, myths and cultural practices. This is an opportunity to produce an evocative film which challenges the stereotypes, delights our senses and adds to our understanding of life as it has been lived on the southern tip of the African continent.

TREATMENT

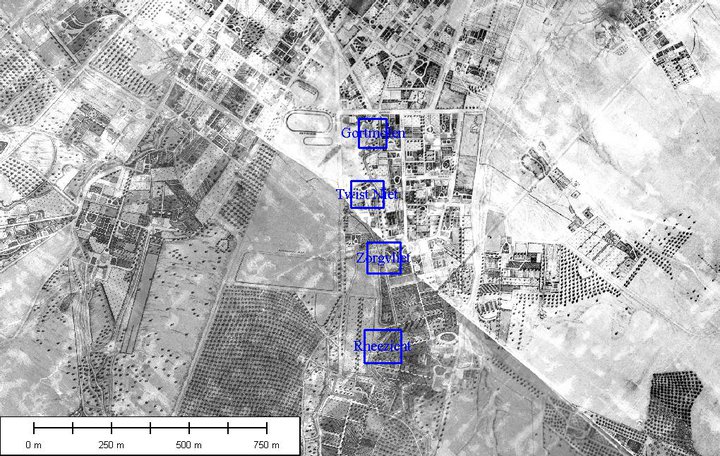

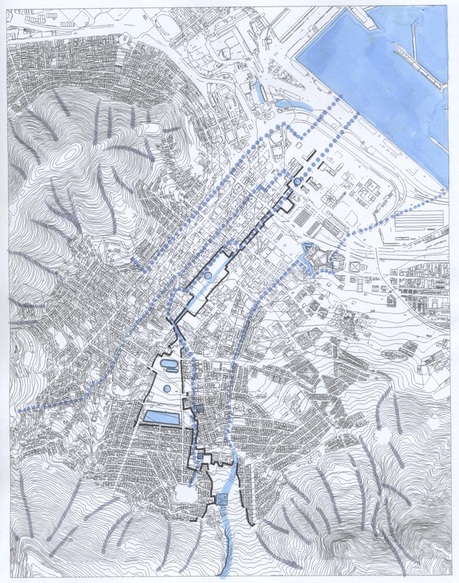

Cape Town's mainlines of wasted water resources. Map by Caron von Zeil, 2004.

The Style of the film will be poetic, multi-voiced and multi-layered, for here we are presenting a journey that follows the waters of Table Mountain as they make their way to the sea. This is a journey that is made visible even in places where the rivers course is under ground. It is also a journey through time as the narrative voices reveal a social history of Cape Town that is as surprising as it is informative. Adopting a personalised, ruminative tone, a series of stories emerges which reflect the changing relationship we have towards these waters. Utilising an off-camera narrative voice, the film avoids talking heads. Extensive research provides the basis for the narrated script, but this is deliberately not an interview driven film.

The camera will follow the water, moving sometimes above ground and at other times below the ground. This not only mirrors the physical movement of the water itself, but also corresponds with the narrative shift between present and past. Manhole covers provide the portals through which the camera moves between the two. Sometimes the camera will emerge into the light of day via a series of superimposed archival images that signpost different historical moments. Reconstructions, done in a minimal way that evokes rather than fully enacts the past, will provide another visual layer for historical voices.

Cameo pieces of installation and performance art enhance the effect of reflecting the past in contemporary ways, as the ‘audience’ perambulates along the route, rediscovering the city’s lost water heritage sites and thus forming a cognitive map of the city’s vital ecological and cultural link between the mountain and the sea.

The film follows the passage of the waters detailing a variety of ‘lost spaces’, leading the viewers along ‘the path of least resistance’ - from Table Mountain to Duncan Dock, reclaiming the city’s connection to this water. This is a 6.7km downhill journey along the city’s old waterways and between two World Heritage Sites: Table Mountain and Robben Island. These waters are the key to understanding and appreciating the natural, social and cultural history - the very meaning of settlement in the Mother City - the founding city of Cape Town.

The camera will follow the water, moving sometimes above ground and at other times below the ground. This not only mirrors the physical movement of the water itself, but also corresponds with the narrative shift between present and past. Manhole covers provide the portals through which the camera moves between the two. Sometimes the camera will emerge into the light of day via a series of superimposed archival images that signpost different historical moments. Reconstructions, done in a minimal way that evokes rather than fully enacts the past, will provide another visual layer for historical voices.

Cameo pieces of installation and performance art enhance the effect of reflecting the past in contemporary ways, as the ‘audience’ perambulates along the route, rediscovering the city’s lost water heritage sites and thus forming a cognitive map of the city’s vital ecological and cultural link between the mountain and the sea.

The film follows the passage of the waters detailing a variety of ‘lost spaces’, leading the viewers along ‘the path of least resistance’ - from Table Mountain to Duncan Dock, reclaiming the city’s connection to this water. This is a 6.7km downhill journey along the city’s old waterways and between two World Heritage Sites: Table Mountain and Robben Island. These waters are the key to understanding and appreciating the natural, social and cultural history - the very meaning of settlement in the Mother City - the founding city of Cape Town.

THEMES

|

The film will highlight the different ways that water has been utilised, wasted and polluted in times past and present and the implications for the future. What follows below are ‘moments’ in the film that correspond to the physical, spiritual and cultural impact that water has made on the collective memory of the city. |

|

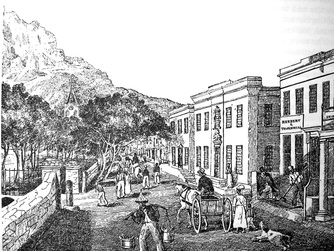

WATER UTILISED

The early streets ran parallel and at right angles to the streams that flowed from the mountain to the sea. Later, these streams were formalized and directed into ‘grachte’ (canals). For example the Heerengracht - today Adderley Street, was the first principal street of the settlement, following the course of the Varsche River to the fort. It was threaded by a double streamlet, with tiny bridges crossing at intervals. It ran through the town centre and continued the axis of the Company’s Garden linked by way of an old gateway, was lined with stoeped townhouses of the burghers and at its foot was the wooden jetty. By 1767 the street had been widened into a fashionable promenade. It was described by a traveller in 1778 as “the most beautiful street or canal, bordered with oaks, along which are built the finest houses.” The mills stood between the town and the mountain, the water was led into the mills in wooden pipes raised on wooden supports. In the 1830 census, it was recorded that there were six functional mills at the foot of Table Mountain. In the Platterklip Stream, what was once a riverbed is now a clearing in the trees, where a circle of rocks lie. This is where Slaves took the population’s laundry. After the emancipation of the Slaves in 1834, their descendants continued to launder at the Platteklip. The Washerwomen would clatter up the mountain in their ‘kaperrangs’ (clogs). Early in the afternoon they would leave their washing and dance to improvised music. Then, as twilight began to creep through the pines, they would march with their bundles down the path alongside the now crumbling slave walls of the Oranjezicht and Rheezicht estates. 'On one such occasion, an attractive Malay girl, the wife of an Hafiz, named Abdul Malik, lost the ring her husband sometimes let her wear, while washing clothes at Platteklip Gorge. She and her friends searched high and low along the banks, but the ring was never found again...... The ring had been given to Abdul by a great scholar under whom Abdul studied Islam. The aged scholar considered him to be his best scholar; and besides bestowing much love upon him, gave him a ring which he was always to wear on his finger. The significance of the ring was never understood, until one day when he went to have his head shaved according to Islamic rule. The barber found that the razor would not cut. After attempts with a second razor had also failed, someone in the shop suggested that Abdul might be wearing a charm, guaranteed to prevent his being harmed by a knife. Puzzled, Abdul removed the ring and experienced no difficulty being shaved. On occasions, the Hafiz’s wife found that when she was wearing the ring, she was unable to cut anything with a blade which seemed to be magically turned away when brought near her. The ring was lost. The search was fruitless. Tradition says that the Hafiz’s magic ring will be found again, one day...' -- In an unpublished manuscript: "From Rivulets to Reservoirs", by Joe Lison. Indeed, a ring was (perhaps) found in 2006, by an American scholar, Dr. Elizabeth Grzymala-Jordan. Her dig revealed plentiful artefacts - enough to fill 34 boxes. Every year, on December 1st, commemorating the abolishment of slavery, there is a commemorative procession of women retracing the steps of their Slave ancestors. Images of women moving through the streets of Cape Town will be used in conjunction with photographs of Slave women carrying bundles of laundry on their heads. Initially, Cape Town had been supplied with gaslight. This changed when a small electric lighting station was established at the western end of the Molteno Reservoir. The German firm of Siemens and Hulske supplied the power plant and in 1894 began laying the first underground cables. In 1895, the Graaff Hydro-Powered Electric Lighting Station of the Cape Town Corporation was officially inaugurated as the generating station of the lighting installation. The structure still stands today as a fine example of early industrial architecture, but no longer serves this function and is falling into disrepair. Yet, the flow of the spring water, together with the elevation at which it falls from, has the capacity to generate enough energy to power the street lighting and public spaces of the City Bowl. |

|

|

|

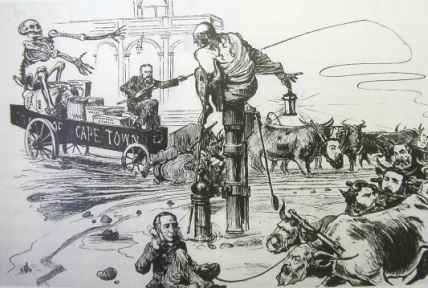

WATER POLLUTED

The mills had been the cogs of industry, all but two of them powered by water. By the time the Bubonic Plague hit Cape Town and water was forced underground, these mills became redundant – as did the water, making its way to the sea via sewers and storm water channels. The ‘grachte’ had become the dumping place for the town’s rubbish. Thus, a systematic programme of arching over and enclosing the canals was initiated in 1838, directly changing the character of old Cape Town. At first a number of bridges were built over the canals and some canals paved. A poem by Willian Bridekirk, published in May 1825, describes: “Canals, thro’ some of the streets flow.

Which stink confoundly you must know; And serve so handy for lazy wenches, To cast therein their slop-pail stenches. Some sluts, besides the above named slop, Other burdens have been known to drop Into these reservoirs of pollution”. Eventually the majority of the grachte had been replaced by brick sewers. By the end of the 1860s, the last stretch of the Heerengracht had been covered and the street, renamed Adderley Street. In 1901, the last of the open water courses was closed, in District Six.

The City Bowl’s current water resources once sustained 111 000 people (and passing trade). Today, only 55 000 persons live in this geographical area, due to the Apartheid legacy of forced removals, which saw 66,000 people forcibly removed from District Six. Today, all of the earlier water resources are wasted through the sewer and storm water system and the city's water is piped in from the food-growing region, as mountain run-off and spring water are currently polluted and wasted. In Cape Town, water and land have not been regarded as being dependant on one another, and so although legislation exists to protect the water, due to the land parcels not being regarded as part of that ecological system many have been privatised, and polluted. The current situation is one of 'hydrocide', is a term coined by Lundqvist - to describe water scarcity, due to social misuse. |

|

WATER: LINKS BETWEEN PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

The Golden Acre Shopping Mall was constructed on the original shoreline, the previous frontier between the city and the sea, at the very spot where European colonialists and Slaves disembarked. As the foundations were dug, they revealed the earliest dam and sluice that was built to supply the passing trade. Previously unseen Super8 film footage from the early 1970s documents the construction of the Golden Acre, dramatically capturing the impact of the water on the site and the archaeological remains of the very site where the ships filled their caskets. Archive footage filmed in the 1980’s shows the clash at the Golden Acre between Anti-Apartheid activists and police using whips and water cannons, shooting purple spray at demonstrators. Photographs of the excavation at the Cape Town train station for the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, revealed the timber from the original old wooden jetty of the early 1600s; an old ship's anchor and a British water well. This was quickly and deliberately covered. The missed opportunity to reveal the ancient entrance to the city by sea faring nations where South Africa’s European and Slave ancestors landed, represented a closing of a frontier at a time when so many eyes were focused on the city. In the rush to complete construction before the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, the site was backfilled and covered over. In the words of Archaeologist, Dr. Antonia Malan: "It was here that sea voyagers stepped ashore - whether freely or not, healthy or sick or dying - it was the umbilical cord that sustained passing ships with fresh food and water - and conducted vital supplies to the struggling settlement - from where indigenous and foreign exiles and convicts were offloaded and shipped to Robben Island - where famous and infamous travellers disembarked.” When Cape Town had to build a special football stadium to host the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, there was no available water to supply the pitch of the newly built stadium and the toilets for the anticipated 9million visitors to the city, other than piping water from the food growing region. A feasibility report was conducted: ‘City of Cape Town 2010 FIFA WORLD CUP, Feasibility Study: The supply of Irrigation Water to Green Point Common’, Preliminary Investigation Report, May 2008, which stated: “City of Cape Town staff, who have observed the flow from the Main Spring over many years have indicated that it is not sensitive to seasonal changes. These springs therefore have sufficient capacity to provide for not only the irrigation needs of the immediate surroundings, but also the Company’s Gardens which are fed from the lower service reservoir no.2, as well as the full demand from Green Point Common. The Molteno Reservoir has sufficient capacity to provide seasonal storage, even though this is not needed with the adequate flow from the Main Spring and Field of Springs.” And so it is ironic that the very spring which gave rise to the first Environmental Law of South Africa, (Placaat 12 of 1655) not to ‘soil’ the water, should be used to flush the toilets for an event that put Cape Town back on the global map. Placcaat 12 of 1655: “Niet boven de stroom van de spruitjie daer de schepen haer water halen te wassen en deselve troubel te maken”. The vernacular is more fitting: 'Moenie in die water kak nie' (do not make sh-t in the water). On top of water pollution, there is also the fact of water being wasted. Just how much water is wasted can be seen as one spring alone produces enough (potentially potable) water daily to provide every person in the Greater Cape Town Municipal Area with one litre of water per day. |

Mrs. Judy Clark had been officially appointed by the CoCT to visually document the progress of the excavations and construction at the original shoreline of Cape Town. On her deathbed, Mrs. Clark bequeathed this footage to her niece, Mrs. Merry Dewar who kindly donated it to RECLAIM CAMISSA.

In addition, CAMERLAND has generously covered the costs of converting these Super8s to digital format so that the footage may be used in the final edit; and will additionally be used to create snippets as part of RECLAIM CAMISSA's Public Education Campaign. |

The biggest asset in the future of Cape Town’s well being with the onslaught of climate change, is that the mountain is an aquifer. This water is a vital resource for the City of Cape Town and yet it was scrapped from the asset resource register in 1994, the year South Africa was reborn as a democracy.

SCRIPT SAMPLE

The film opens with a sunrise shot of Table Mountain. Clouds carpet the top and pour down the mountain towards the City Bowl. Streams of water cascade down the craggy slopes. A series of close up shots reveal the springs where water is bubbling out of the ground at various points. The sound of flowing water underpins an aerial view of Cape Town as the camera sweeps over the City Bowl and settles on the harbour and the sea...Water flows out of a spring flowing downhill over sand and over rocks. Shot in close up, and after a series of images, there is a tracking shot that follows the flow of the water. Superimposed over this, ghost-like, we see groups of Khoisan people, circles within circles – these are the earliest inhabitants of the Cape, engaged in an ancient ritual, the 'Circle of the Water'. The innermost ring of people, a harmonious group, is encircled by a trench into which the waters flow...Close up shots of

water spraying as it courses underground. The sound the water makes is angry and

percussive anticipating the conflict that ensued between Europeans and the

indigenous population...

SUMMARY

Journeying through the ‘lost spaces’ associated with Cape Town’s waterways, the global story of WATER, LAND and HUMANKIND unfolds. As we follow the path of these waters from mountain to ocean, we reveal that water follows the path of least resistance - it has no boundaries. As the environmental crisis escalates worldwide, urgent and thoughtful steps need to be taken to reduce water loss, waste and pollution. Strengthened community awareness and participation, collaborative approaches and an empowered citizenry are evermore essential - this film serves above all, to not only inform but to rekindle our profound connection and respect for water.

Mark J. Kaplan - Director / Producer

Mark Kaplan

Mark is a director and producer with a special interest in human rights and sports documentaries.

He has been a documentary filmmaker for the past 25 years - an extremely eventful and spiritually enriching journey that began at the University of Cape Town, where he was the first Executive Director of a community video training project - the first in South Africa to offer video based documentary training and facilities to the disadvantaged. This resulted in his being detained and held in solitary confinement, released without charges and ultimately deported to Zimbabwe, in August 1982.

His formal training in Video and Film Production took place at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he completed a Master of Science in Visual Studies (1983-85).

He returned to Zimbabwe in 1985 and set up Capricorn Video, which was both a production base and a regional training hub to filmmakers throughout the Southern African region. He was one of the founding members of Southern Africa Communications for Development (SACOD), which continues as a forum for filmmakers from the region. During his 7 years in Zimbabwe, he directed, produced and edited a large number of productions that went on international circuit and received wide recognition and acclaim.

Mark has been back in South Africa for the past 21 years and in this time has produced two 13-part Pan African Television and Radio documentary series, Africa: Search for Common Ground; and African Renaissance - for the SABC. The series won a Silver Award at the Columbus International Film and Video Festival in 1997. In addition, Mark has directed a range of films around the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which have won numerous international film awards, including:

He has been a documentary filmmaker for the past 25 years - an extremely eventful and spiritually enriching journey that began at the University of Cape Town, where he was the first Executive Director of a community video training project - the first in South Africa to offer video based documentary training and facilities to the disadvantaged. This resulted in his being detained and held in solitary confinement, released without charges and ultimately deported to Zimbabwe, in August 1982.

His formal training in Video and Film Production took place at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he completed a Master of Science in Visual Studies (1983-85).

He returned to Zimbabwe in 1985 and set up Capricorn Video, which was both a production base and a regional training hub to filmmakers throughout the Southern African region. He was one of the founding members of Southern Africa Communications for Development (SACOD), which continues as a forum for filmmakers from the region. During his 7 years in Zimbabwe, he directed, produced and edited a large number of productions that went on international circuit and received wide recognition and acclaim.

Mark has been back in South Africa for the past 21 years and in this time has produced two 13-part Pan African Television and Radio documentary series, Africa: Search for Common Ground; and African Renaissance - for the SABC. The series won a Silver Award at the Columbus International Film and Video Festival in 1997. In addition, Mark has directed a range of films around the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which have won numerous international film awards, including:

- An Emmy Award for "A Lion’s Trail", which tells the story of South Africa's most famous song, "Mbube" - in 2005.

- Best International Documentary in 1999 at The One World Media Awards in London; and Best of the Fest at the Vermont International Film and Television Awards in 2000, for "Where Truth Lies".

- In 2004, "Between Joyce and Remembrance" was selected for INPUT in Barcelona and was the opening night film in New York, for the '10 Years of Freedom Festival' of South African Films. In 2006 it received the Award of Excellence at the American Anthropological Association Film and Video Festival.

Caron von Zeil - Consultant / Associate Producer

Caron von Zeil

Since June 2004, Caron has been engaged in the many facets of Cape Town's water - a resource that was a necessity to seafaring nations and put Cape Town on the global map. It could be said, that it was this water that gave rise to globalisation.

Despite being born in the Namib Desert and spending the first 11 years of her life in the desolate Richtersveld and other parts of Namaqualand - it was not until stranded without water at the foot of the Sierra Largos, in a small coastal village of Oaxaca, Mexico with her one year old son and their German Shepherd Dog, that the vital importance of water became so apparent to her. Enriched by this experience, she undertook a Master's degree in Environmental Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Cape Town. Whilst researching for her thesis, she rediscovered the Water resources which gave rise to the settlement of the Cape, but have become embedded in the urban fabric and buried under the city's streets - lost to humanity.

Intrigued by the cultural stories connected to the waters of Cape Town - stories that tell the history of a nation, different to the one told by history books: "When one uncovers the history of a place, it is through means of title deeds - ownership and power. However, when one uncovers the history of a place through its water, one uncovers the popular history of that place, as throughout time we have all been dependent on this water. As water flows the path of least resistance - it has no boundaries and these stories tell the untold history of Cape Town - the history of all members of our society."

Caron believes it is important to tell these stories as a means to reclaim our common cultural identity, in a country ravaged by an immense painbody due to the country's past of colonialism; slavery; the Boer Wars; and Apartheid - a painbody that will be further exacerbated by climate change, unless through emotional intelligence we devise ways to engage our citizenry in the part they can play to change; and to give water the dignity it deserves. As the Founder of RECLAIM CAMISSA, Caron's aim is to assist her fellow citizens in reclaiming this vital resource and the public spaces associated with the system, in the hope that Capetonians will be enabled to emerge with a common cultural identity that reflects the diversity of the country's 'rainbow nation'.

Despite being born in the Namib Desert and spending the first 11 years of her life in the desolate Richtersveld and other parts of Namaqualand - it was not until stranded without water at the foot of the Sierra Largos, in a small coastal village of Oaxaca, Mexico with her one year old son and their German Shepherd Dog, that the vital importance of water became so apparent to her. Enriched by this experience, she undertook a Master's degree in Environmental Planning and Landscape Architecture at the University of Cape Town. Whilst researching for her thesis, she rediscovered the Water resources which gave rise to the settlement of the Cape, but have become embedded in the urban fabric and buried under the city's streets - lost to humanity.

Intrigued by the cultural stories connected to the waters of Cape Town - stories that tell the history of a nation, different to the one told by history books: "When one uncovers the history of a place, it is through means of title deeds - ownership and power. However, when one uncovers the history of a place through its water, one uncovers the popular history of that place, as throughout time we have all been dependent on this water. As water flows the path of least resistance - it has no boundaries and these stories tell the untold history of Cape Town - the history of all members of our society."

Caron believes it is important to tell these stories as a means to reclaim our common cultural identity, in a country ravaged by an immense painbody due to the country's past of colonialism; slavery; the Boer Wars; and Apartheid - a painbody that will be further exacerbated by climate change, unless through emotional intelligence we devise ways to engage our citizenry in the part they can play to change; and to give water the dignity it deserves. As the Founder of RECLAIM CAMISSA, Caron's aim is to assist her fellow citizens in reclaiming this vital resource and the public spaces associated with the system, in the hope that Capetonians will be enabled to emerge with a common cultural identity that reflects the diversity of the country's 'rainbow nation'.

"When the source of water is local, known and honoured culturally, people understand the importance of water to their health and thus, they care for this source." -- Betsy Damon, Keepers of the Water

RECLAIM CAMISSA seeks funding to make this documentary.

If you are able to contribute to the ongoing collection of footage, please donate to The RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010, indicating "doccie" as your reference, via our bank account:

Account Name: Reclaim Camissa Trust

Account Number: Standard Bank 070091900

Account Type: Business Cheque Account

Branch Name: Standard Bank, Thibault Square Branch, South Africa

Branch Code: 020009

Alternatively, any organisation; institution; corporation or individual interested in funding this documentary - please contact us via [email protected] in order to obtain a full copy of the proposal and budget.

If you are able to contribute to the ongoing collection of footage, please donate to The RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010, indicating "doccie" as your reference, via our bank account:

Account Name: Reclaim Camissa Trust

Account Number: Standard Bank 070091900

Account Type: Business Cheque Account

Branch Name: Standard Bank, Thibault Square Branch, South Africa

Branch Code: 020009

Alternatively, any organisation; institution; corporation or individual interested in funding this documentary - please contact us via [email protected] in order to obtain a full copy of the proposal and budget.

© COPYRIGHT

ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED by THE RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010.

The use of material on this page is permitted with acknowledgement of the source and prior written consent - contactable via [email protected]

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.

ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED by THE RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010.

The use of material on this page is permitted with acknowledgement of the source and prior written consent - contactable via [email protected]

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.