THE FIELD OF SPRINGS

This project was under negotiation - for access to the land and thus the Water and is at the the Design Development stage.

A critical path has been set up, together with a programme - for the stages throughout the process and research and data collection, both quantitative and qualitative, with regard to the groundwater continues.

A critical path has been set up, together with a programme - for the stages throughout the process and research and data collection, both quantitative and qualitative, with regard to the groundwater continues.

|

THE SPRINGS OF TABLE MOUNTAIN

The occurrence of springs along the slopes of Table Mountain are due to the exposure of the contact zone between the porous Sandstone and the impermeable Granite. Click on the links below, to find the following information:

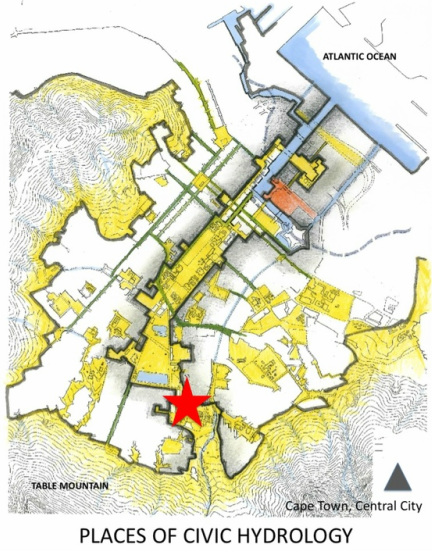

RECLAIM CAMISSA has located thirty-two artesian springs in the Table Valley Catchment Area (City Bowl) of Cape Town. According to archival records, there are thirty-six in this geographic area, and many more throughout the Peninsula. Only thirteen of the springs in this specific area are currently listed by the municipality. Quantitatively, the largest of the City Bowl's springs, is the Stadtsfontein - with 2.77million litres of Water flowing, daily. It is without a doubt that this spring is Cape Town's very raison d'etre - it was from this spring that Water was led down to the old wooden jetty, where the caskets were filled for the ships of seafaring nations, since the 1650s. |

The Stadtsfontein and the Field of Springs

|

A ongoing photo essay on the Field of Springs, is available here

|

|

The waters from this spring, affected the first Environmental Law of South Africa - Placcaat 12 of 1655:

“Niet boven de stroom van de spruitjie daer de schepen haer water halen te wassen en deselve troubel te maken”.

A brief history of 'The Field of Springs'

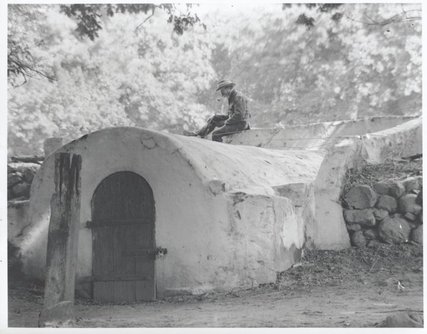

The Stadtsfontein dates back to 1686, where there was a Water collecting chamber above the Oranjezicht farm to the Castle of Good Hope. This spring supplied Cape Town’s first Water pipe before 1769; and was covered with a vault in 1813. Below it was another collection chamber for the springs in the area, today the Water from three other springs flows into this chamber, erroneously called the 'New Main Spring', it was built in 1853.

The Stadtsfontein was situated on the Oranjezicht farm, and the Water was controlled by the van Breda family. Though the Water flowed through other properties van Breda controlled the Water and was given full Water rights in 1769. Van Breda’s neighbours complained bitterly, and after a commission was appointed it was decided to install a system of sluices (lei-water slote) to regulate the access to Water. During the 1800s the structure around the Stadsfontein was built and the Water supply was formalised in a small structure on the Oranjezicht farm. This was for the collection of all 12 springs on the farm; and from that point the Water was led in an iron pipe to the reservoir under the Hurling “Swaai” pump, on Prince Street.

Later, after the lower service reservoirs were built, Water was supplied by a number of springs on the side of Table Mountain: Platteklip, Stadtsfontein, Lammetjies, Vineyard, Waterhof and Kotze (on the Leeuwenhof Estate). This was a substantial supply, for in the year 1896-1897, 811 000 000 imperial gallons of Water were run off. The elevation at which the Water was stored made it very valuable for hydraulic power, “an effective 750 horse power can be obtained for every 12 hours every day throughout the whole year.” (In Thomas Stewart, 1897)

In 1811, the waterhouse was built in Hof Street. The reservoir was 200 feet long, 22 feet broad and 10 feet deep. Water was led into the house from the Stadtsfontein, from Platteklip Stream and from Waterhof spring. This structure was demolished in the 1900s.

Although a scheme had been proposed, twice since the 1850s, for storing and conducting the Water collected on the mountain, to the town (first by Fletcher in 1858; and then by Gamble almost 20 years later), no steps had been taken to carry it out, necessary as it was, because the colony lacked funds. In 1813, the Burgher Senate was empowered to impose and raise a tax, necessary to supply town with Water in pipes. Water in cast iron pipes was made available by April 1814.

Even though the lower service reservoirs, built in 1856 and 1860 were effective in supplying water for the growing population, it was not enough and in 1859 a Bill was published with a number important clauses one which effected the Oranjezicht farm considerably. It stated that “all fountains, streams and other sources of Water supply within the boundaries of the Municipalities of Cape Town and Green Point… shall be and are hereby solely and exclusively vested in the board of commissioners constituted by this act.”

The effect of the Water Bill published was that the Water Board (created to manage all Water in the municipality, and functioned independently from the municipality) would in effect own the Water on the Oranjezicht farm. In order to do this, the board had to obtain the ground on which the springs were situated. This was easier said than done as an agreement was signed which stated that “the whole of the Estate Oranjezicht shall for ever - remain an inalienable hereditary family estate of the family van Breda”.

An Act in 1861 indicated that all the Water on the farm shall be placed in charge of the Superintendent of Waterworks. Obviously van Breda petitioned against this, but to no avail and the Act was accepted and passed. The last step in obtaining all the access to Water was Act 23, of 1882 which was to make a provision to release the portion of the farm on which the Stadtsfontein stood, and that relative compensation should be paid to the owners of the farm.

By 1868, the municipality had acquired a portion of the Waterhof Estate, the Kotze spring (on the Leeuwenhof Estate) and the mills along the old mill stream, in this way Water pipes could be spread over the whole of Cape Town, covering 26 miles of streets.

In 1887, work was started to construct a tunnel (Woodhead Tunnel) – a major undertaking, involving the driving of a tunnel 700m through Table Mountain from Disa Gorge to Slangolie Ravine. Besides the tunnel, many miles of pipeline and a number of tall aqueducts had to be constructed to carry the water over Kloofnek and down to Molteno Reservoir, where Graaff's Hydro-Electric Station was built in 1895 - supplying Cape Town with electrical lights, whilst London still operated gas lamps.

Once this occurred, the waterless estate of Oranjezicht became quite useless to the owners, who paid urban rates of £600 per annum. The Van Breda’s were compensated £832. The farm was suddenly not viable and they now had to pay for the Water they needed for irrigation. Thus, the family were persuaded to sell the estate for £40 000 to a speculative villa building company. By 1900, the area became a suburb of tree lined avenues. The family continued to live on the remaining farm, but with time more and more portions were sold and the area became the residential suburb of Oranjezicht.

The springs and sources of water on the estate Oranjezicht were declared to be vested in the Town Council, with the right to dig, bore, excavate, open up and carry out all works as may be found necessary to construct filtering beds and other works required to collect the waters and to lay pipes so as to lead out the waters for the use of the city of Cape Town.

By 1994, this water was scrapped from the asset resource register of the city, and today flows wasted under the streets of the Central Business District of Cape Town.

As stated in the ‘City of Cape Town 2010 FIFA WORLD CUP, Feasibility Study: The supply of Irrigation Water to Green Point Common’, Preliminary Investigation Report, May 2008:

"The flow from these springs has been monitored, with a flow from the New Main Spring measured as being some 28l/s. Our own investigations at the end of summer, 2008 showed that there are several other springs which have been formalised, with flow discharged below the New Main Spring collection chamber. This combined flow was measured at a point where it currently flows down a 914mm internal diameter brick stormwater pipe. This flow, well in excess of 40l/s. City of Cape Town staff, who have observed the flow from the Main Spring over many years have indicated that it is not sensitive to seasonal changes. These springs therefore have sufficient capacity to provide for not only the irrigation needs of the immediate surroundings, but also the Company’s Gardens which are fed from the lower service reservoir no.2, as well as the full demand from Green Point Common. The Molteno Reservoir has sufficient capacity to provide seasonal storage, even though this is not needed with the adequate flow from the Main Spring and Field of Springs.”

And so it is ironic that the very spring, which caused the demise of the Oranjezicht Farm, in the name of development - should give rise to the resurrection of the old 'structure' of Cape Town, due - once again - to the need for Water. Sadly, in reality - this is not what occurred, though a portion of the Water has been re-directed.

The Stadtsfontein was situated on the Oranjezicht farm, and the Water was controlled by the van Breda family. Though the Water flowed through other properties van Breda controlled the Water and was given full Water rights in 1769. Van Breda’s neighbours complained bitterly, and after a commission was appointed it was decided to install a system of sluices (lei-water slote) to regulate the access to Water. During the 1800s the structure around the Stadsfontein was built and the Water supply was formalised in a small structure on the Oranjezicht farm. This was for the collection of all 12 springs on the farm; and from that point the Water was led in an iron pipe to the reservoir under the Hurling “Swaai” pump, on Prince Street.

Later, after the lower service reservoirs were built, Water was supplied by a number of springs on the side of Table Mountain: Platteklip, Stadtsfontein, Lammetjies, Vineyard, Waterhof and Kotze (on the Leeuwenhof Estate). This was a substantial supply, for in the year 1896-1897, 811 000 000 imperial gallons of Water were run off. The elevation at which the Water was stored made it very valuable for hydraulic power, “an effective 750 horse power can be obtained for every 12 hours every day throughout the whole year.” (In Thomas Stewart, 1897)

In 1811, the waterhouse was built in Hof Street. The reservoir was 200 feet long, 22 feet broad and 10 feet deep. Water was led into the house from the Stadtsfontein, from Platteklip Stream and from Waterhof spring. This structure was demolished in the 1900s.

Although a scheme had been proposed, twice since the 1850s, for storing and conducting the Water collected on the mountain, to the town (first by Fletcher in 1858; and then by Gamble almost 20 years later), no steps had been taken to carry it out, necessary as it was, because the colony lacked funds. In 1813, the Burgher Senate was empowered to impose and raise a tax, necessary to supply town with Water in pipes. Water in cast iron pipes was made available by April 1814.

Even though the lower service reservoirs, built in 1856 and 1860 were effective in supplying water for the growing population, it was not enough and in 1859 a Bill was published with a number important clauses one which effected the Oranjezicht farm considerably. It stated that “all fountains, streams and other sources of Water supply within the boundaries of the Municipalities of Cape Town and Green Point… shall be and are hereby solely and exclusively vested in the board of commissioners constituted by this act.”

The effect of the Water Bill published was that the Water Board (created to manage all Water in the municipality, and functioned independently from the municipality) would in effect own the Water on the Oranjezicht farm. In order to do this, the board had to obtain the ground on which the springs were situated. This was easier said than done as an agreement was signed which stated that “the whole of the Estate Oranjezicht shall for ever - remain an inalienable hereditary family estate of the family van Breda”.

An Act in 1861 indicated that all the Water on the farm shall be placed in charge of the Superintendent of Waterworks. Obviously van Breda petitioned against this, but to no avail and the Act was accepted and passed. The last step in obtaining all the access to Water was Act 23, of 1882 which was to make a provision to release the portion of the farm on which the Stadtsfontein stood, and that relative compensation should be paid to the owners of the farm.

By 1868, the municipality had acquired a portion of the Waterhof Estate, the Kotze spring (on the Leeuwenhof Estate) and the mills along the old mill stream, in this way Water pipes could be spread over the whole of Cape Town, covering 26 miles of streets.

In 1887, work was started to construct a tunnel (Woodhead Tunnel) – a major undertaking, involving the driving of a tunnel 700m through Table Mountain from Disa Gorge to Slangolie Ravine. Besides the tunnel, many miles of pipeline and a number of tall aqueducts had to be constructed to carry the water over Kloofnek and down to Molteno Reservoir, where Graaff's Hydro-Electric Station was built in 1895 - supplying Cape Town with electrical lights, whilst London still operated gas lamps.

Once this occurred, the waterless estate of Oranjezicht became quite useless to the owners, who paid urban rates of £600 per annum. The Van Breda’s were compensated £832. The farm was suddenly not viable and they now had to pay for the Water they needed for irrigation. Thus, the family were persuaded to sell the estate for £40 000 to a speculative villa building company. By 1900, the area became a suburb of tree lined avenues. The family continued to live on the remaining farm, but with time more and more portions were sold and the area became the residential suburb of Oranjezicht.

The springs and sources of water on the estate Oranjezicht were declared to be vested in the Town Council, with the right to dig, bore, excavate, open up and carry out all works as may be found necessary to construct filtering beds and other works required to collect the waters and to lay pipes so as to lead out the waters for the use of the city of Cape Town.

By 1994, this water was scrapped from the asset resource register of the city, and today flows wasted under the streets of the Central Business District of Cape Town.

As stated in the ‘City of Cape Town 2010 FIFA WORLD CUP, Feasibility Study: The supply of Irrigation Water to Green Point Common’, Preliminary Investigation Report, May 2008:

"The flow from these springs has been monitored, with a flow from the New Main Spring measured as being some 28l/s. Our own investigations at the end of summer, 2008 showed that there are several other springs which have been formalised, with flow discharged below the New Main Spring collection chamber. This combined flow was measured at a point where it currently flows down a 914mm internal diameter brick stormwater pipe. This flow, well in excess of 40l/s. City of Cape Town staff, who have observed the flow from the Main Spring over many years have indicated that it is not sensitive to seasonal changes. These springs therefore have sufficient capacity to provide for not only the irrigation needs of the immediate surroundings, but also the Company’s Gardens which are fed from the lower service reservoir no.2, as well as the full demand from Green Point Common. The Molteno Reservoir has sufficient capacity to provide seasonal storage, even though this is not needed with the adequate flow from the Main Spring and Field of Springs.”

And so it is ironic that the very spring, which caused the demise of the Oranjezicht Farm, in the name of development - should give rise to the resurrection of the old 'structure' of Cape Town, due - once again - to the need for Water. Sadly, in reality - this is not what occurred, though a portion of the Water has been re-directed.

PILOT PROJECT PROPOSAL: 'The Field of Springs'

Water security is a major constraining factor in the future economic growth of Cape Town; and the South Western Cape in particular is critically exposed to Water scarcity issues within the next decade.

The essence of the pilot project of RECLAIM CAMISSA at the Field of Springs would result in the capture and use of more than 6 million litres of potable water, daily that is currently not utilised within the municipal water supply nor ecological system, as it is currently piped out to sea via subterranean tunnels. The project would therefore positively impact on water security, and assist in reduced risks and increased revenues with regard to water supply management in the city as a whole.

It is envisaged that once the water from the initial 5 springs identified, is being treated and captured for use as part of the City of Cape Town’s potable water supply; or as part of the economic model for further water reclamation projects, the methodology could be rolled out to other areas of the Greater Cape Town Municipal Area.

The benefits of the Pilot Project - relying on the flow data of 2 out of 5 of the springs - translates to:

1. R8.5m or R16.6m per annum, if one uses the lowest residential water pricing tariff of R5.85 per kl or R11.42 per kl for commercial and industrial usage as published in the City’s Integrated Development Plan.

2. Revenue generated by the capture and sale of this water could be utilised to develop other aspects of RECLAIM CAMISSA as subsequent self funded initiatives (for instance the bottling thereof and distribution within the city by means of a ‘bicycle brigade’) that would contribute towards skills upliftment and job creation; and hence contribute significantly to the showcasing of a green city and green economy.

3. The project in capturing potable water at source for domestic and/or commercial use would enable the city to embark on a project, by satisfying water needs closer to source, with the resultant reduction in infrastructural expansion and maintenance; and with the simultaneous reduction in disaster risk management strategies necessitated by water catchment management areas that are geographically remote from the point of consumption. This would translate into a reduced treatment and supply cost per kl compared with conventional water supply strategies. Particularly relevant here, is the current 36.8% national loss of non-revenue water, as a result of infrastuctural leakages - which could be resolved by water catchment management within the geographical area.

4. The water captured by RECLAIM CAMISSA at the 5 springs thus identified out of a possible 25, equates to the free basic water supply at 20,277 homes without impact on the water resources as this is water not currently captured. As such the project benefits the wider Cape Town community notwithstanding its geographic positioning within an affluent suburb.

This, aside from the benefits noted in the Pilot Project proposal :

The essence of the pilot project of RECLAIM CAMISSA at the Field of Springs would result in the capture and use of more than 6 million litres of potable water, daily that is currently not utilised within the municipal water supply nor ecological system, as it is currently piped out to sea via subterranean tunnels. The project would therefore positively impact on water security, and assist in reduced risks and increased revenues with regard to water supply management in the city as a whole.

It is envisaged that once the water from the initial 5 springs identified, is being treated and captured for use as part of the City of Cape Town’s potable water supply; or as part of the economic model for further water reclamation projects, the methodology could be rolled out to other areas of the Greater Cape Town Municipal Area.

The benefits of the Pilot Project - relying on the flow data of 2 out of 5 of the springs - translates to:

1. R8.5m or R16.6m per annum, if one uses the lowest residential water pricing tariff of R5.85 per kl or R11.42 per kl for commercial and industrial usage as published in the City’s Integrated Development Plan.

2. Revenue generated by the capture and sale of this water could be utilised to develop other aspects of RECLAIM CAMISSA as subsequent self funded initiatives (for instance the bottling thereof and distribution within the city by means of a ‘bicycle brigade’) that would contribute towards skills upliftment and job creation; and hence contribute significantly to the showcasing of a green city and green economy.

3. The project in capturing potable water at source for domestic and/or commercial use would enable the city to embark on a project, by satisfying water needs closer to source, with the resultant reduction in infrastructural expansion and maintenance; and with the simultaneous reduction in disaster risk management strategies necessitated by water catchment management areas that are geographically remote from the point of consumption. This would translate into a reduced treatment and supply cost per kl compared with conventional water supply strategies. Particularly relevant here, is the current 36.8% national loss of non-revenue water, as a result of infrastuctural leakages - which could be resolved by water catchment management within the geographical area.

4. The water captured by RECLAIM CAMISSA at the 5 springs thus identified out of a possible 25, equates to the free basic water supply at 20,277 homes without impact on the water resources as this is water not currently captured. As such the project benefits the wider Cape Town community notwithstanding its geographic positioning within an affluent suburb.

This, aside from the benefits noted in the Pilot Project proposal :

- To allow for the site to be the public asset that it should be; re-introducing the ecosystem and bio-diversity.

- To foster public environmental education through various demonstration models, serving as experiments for approaches in the future; including local small-scale hydro-power for utilities on site.

- To create awareness for our local natural and cultural heritage, by providing interactive and recreational public use of the site, public access; public environmental education and integration.

- And to create jobs.

RECLAIM CAMISSA in association with

ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED by THE RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.