"No man ever steps in the same river twice,

For it's not the same river and he's not the same man"

- Heraclitus, Ancient Greek Philosopher.

For it's not the same river and he's not the same man"

- Heraclitus, Ancient Greek Philosopher.

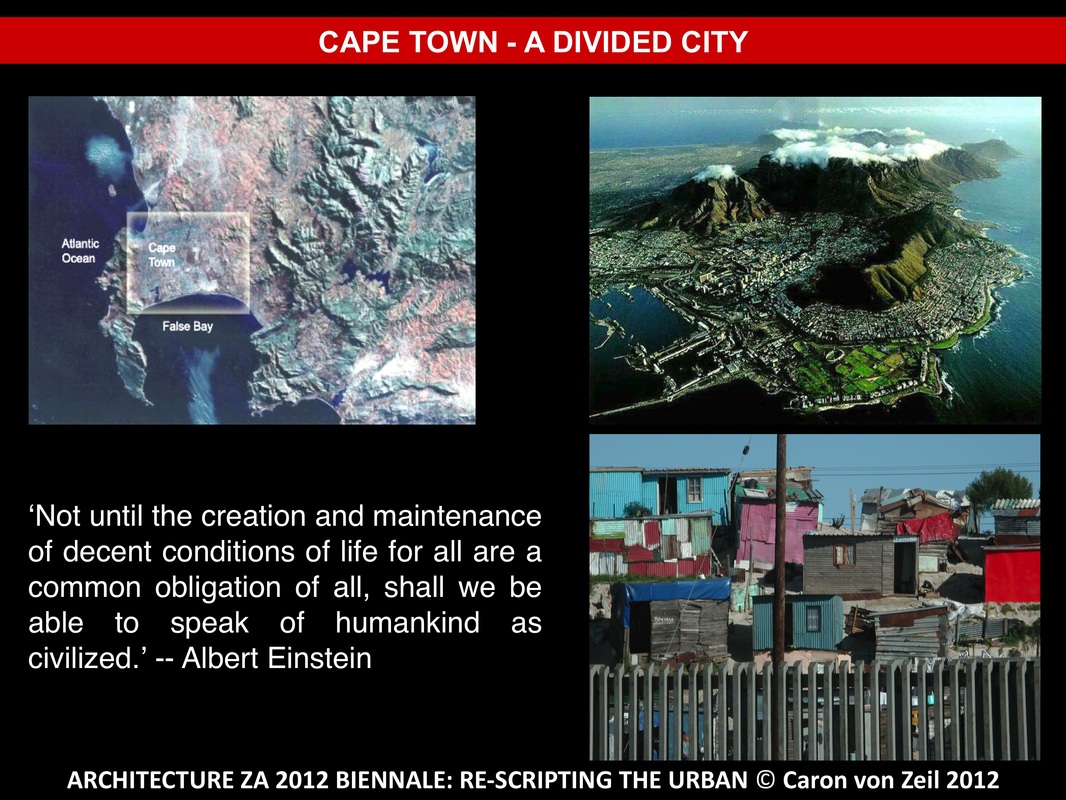

Heritage Day in Cape Town, nestled below Table Mountain, one of the globe’s most iconic images, with the rugged, flat top of the mountain contrasting with the soft table-cloth-cloud spilling over its edges, make it a living monument to the forces that shape it - wind and Water.

Photo credit: Caron von Zeil, 2018.

Water, key to understanding and appreciating the natural history of the Table Valley together with the stories of this Water flowing off the mountain, links the natural to the political and cultural landscapes of the city. The Camissa Water system flows between two World Heritage sites: Table Mountain and Robben Island, and is an authentic illustration of the evolution of the Earth and the origin of life, 3 500million years ago to the present. It is an interactive ecology that reveals a tense relationship between humankind, land and Water - at the frontier of our modern nation. It is a unique system of ecological and historical significance - a cultural landscape - the manifestation of centuries of interaction between people and their natural environment.

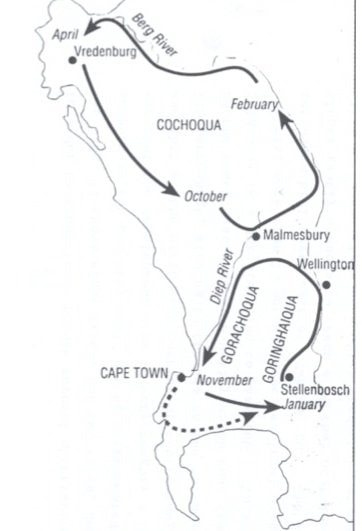

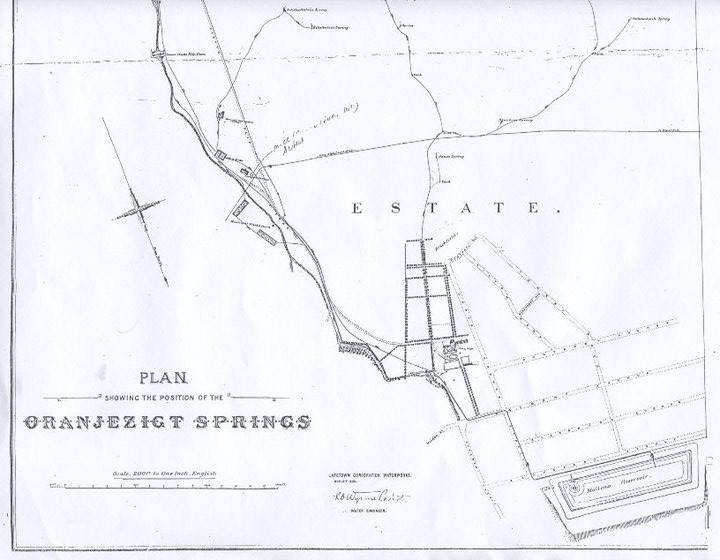

The streams that run from the mountain brought the Khoekhoen here every spring for up to 1500 years before colonial settlement. The springs and streams that flow through the dry summer were the key to farming the land. Water drove the wheels of industry and quenched the thirst of beasts, residents and passing sailors. Until well into the 1900s, the principal economic base for Cape Town, was to supply passing ships, and Water was central to making that feasible.

The streams that run from the mountain brought the Khoekhoen here every spring for up to 1500 years before colonial settlement. The springs and streams that flow through the dry summer were the key to farming the land. Water drove the wheels of industry and quenched the thirst of beasts, residents and passing sailors. Until well into the 1900s, the principal economic base for Cape Town, was to supply passing ships, and Water was central to making that feasible.

Map of the annual Khoi transhumance patterns in and around the Cape Peninsula.

Image source: From Andrew Smith, in “The Making of a City”, by Worden, et al.

Image source: From Andrew Smith, in “The Making of a City”, by Worden, et al.

The unique stories surrounding the sweet waters that flow from a series of artesian springs beneath the iconic Table Mountain are...

‘a symbol of the many trials and tribulations that accompanied the displacement of first nation users, the disparity in society that arises when the privileged are given preferential access, and the subsequent abuse of a resource to the point of collapse.’ - Dr. Anthony Turton.

The story of Table Mountain’s Water is the story of power, of forgotten voices, of people displaced, of slavery and of slavery overturned. It is the story of Water harnessed as well as wasted. As we follow this Water, back and forth in time, we uncover many interwoven stories, alternating between moments of technological ingenuity, stupidity, enlightenment, and barbarism. Throughout, there are the profound links between the past, the present and the future.

‘a symbol of the many trials and tribulations that accompanied the displacement of first nation users, the disparity in society that arises when the privileged are given preferential access, and the subsequent abuse of a resource to the point of collapse.’ - Dr. Anthony Turton.

The story of Table Mountain’s Water is the story of power, of forgotten voices, of people displaced, of slavery and of slavery overturned. It is the story of Water harnessed as well as wasted. As we follow this Water, back and forth in time, we uncover many interwoven stories, alternating between moments of technological ingenuity, stupidity, enlightenment, and barbarism. Throughout, there are the profound links between the past, the present and the future.

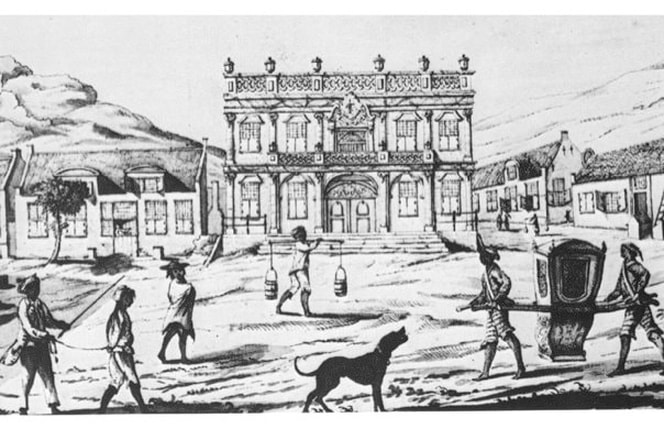

Slave Water carriers on Greenmarket Square.

Image: Cape Archives M166: BURGHERSWACHTPLEIN (1764).

Image: Cape Archives M166: BURGHERSWACHTPLEIN (1764).

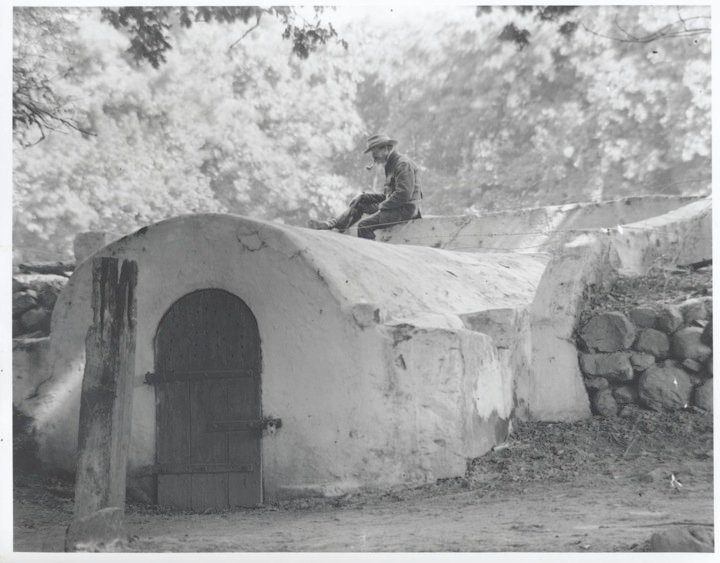

The waters of Table Mountain were both revered and defiled, at times the source of well-being and and at other times a carrier of life-threatening diseases, such as the Smallpox epidemic of 1713. At different points along the water’s course, mills were built and power was generated from the flow. The mills stood between the town and the mountain, the Water was led into the mills in wooden pipes raised on wooden supports. In the 1830 census, it was recorded that there were six functional mills at the foot of Table Mountain.

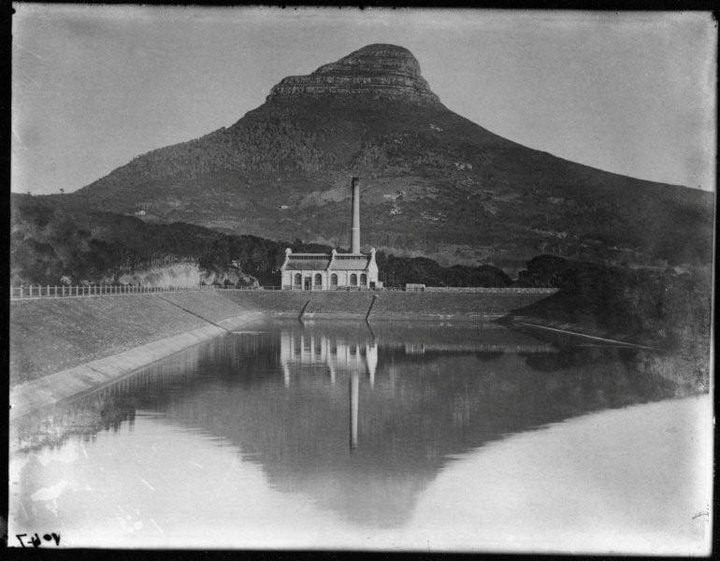

Cape Town, a colonial backwater, an outpost of relative insignificance in the British Empire, utilised its Water to generate electricity for its street lighting, while London still relied on gas lamps. Initially, Cape Town had been supplied with gaslight. This changed when a small electric lighting station was established at the western end of the Molteno Reservoir.

The German firm of Siemens and Hulske supplied the power plant and in 1894 began laying the first underground cables. In 1895, the Graaff Hydro-Powered Electric Lighting Station of the Cape Town Corporation was officially inaugurated as the generating station of the lighting installation. The structure still stands today as a fine example of early industrial architecture, but no longer serves this function and is falling into disrepair.

Cape Town, a colonial backwater, an outpost of relative insignificance in the British Empire, utilised its Water to generate electricity for its street lighting, while London still relied on gas lamps. Initially, Cape Town had been supplied with gaslight. This changed when a small electric lighting station was established at the western end of the Molteno Reservoir.

The German firm of Siemens and Hulske supplied the power plant and in 1894 began laying the first underground cables. In 1895, the Graaff Hydro-Powered Electric Lighting Station of the Cape Town Corporation was officially inaugurated as the generating station of the lighting installation. The structure still stands today as a fine example of early industrial architecture, but no longer serves this function and is falling into disrepair.

There is much to be learnt from the past as we confront the challenges of climate change, such as Water shortages, rising sea levels and storms. The stories of Water in Cape Town are rich in texture, redolent with memories, myths and cultural practices. These stories are evocative and add to our understanding of life as it has been lived on the southern tip of the African continent.

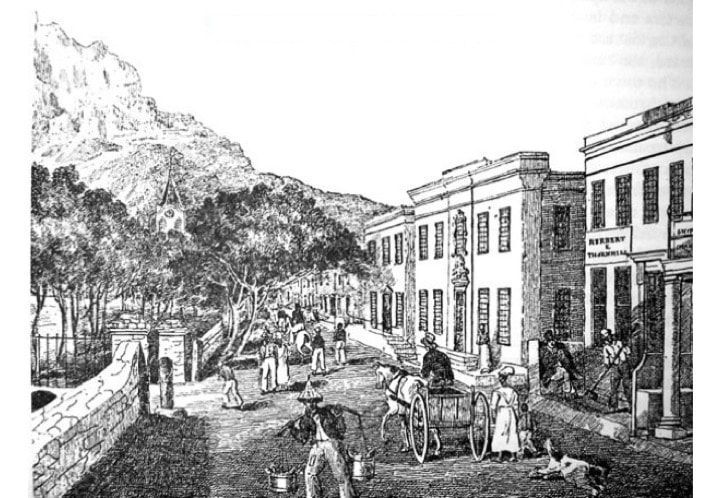

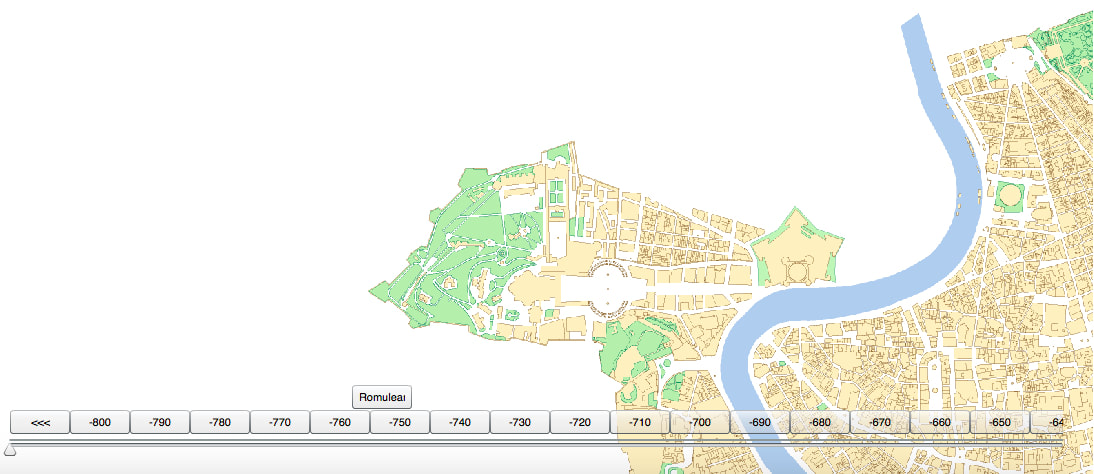

The way streams were channelled down and across valleys, gave the form to land holdings and is the essence of the spatial geometry of Cape Town. The early streets ran parallel and at right angles to the streams that flowed from the mountain to the sea. Later, these streams were formalized and directed into ‘grachte’ (canals).

For example the Heerengracht – today’s Adderley Street, was the first principal street of the settlement, one of 4 rivers that the Dutch named the Varsche River. It was threaded by a double streamlet, with tiny bridges crossing at intervals and ran through the town centre providing the continuity of the axis of the Company’s Garden linked by way of an old gateway, lined with stoeped townhouses of the burghers and at its foot was the wooden jetty. By 1767 the street had been widened into a fashionable promenade. It was described by a traveller in 1778 as “the most beautiful street or canal, bordered with oaks, along which are built the finest houses.”

For example the Heerengracht – today’s Adderley Street, was the first principal street of the settlement, one of 4 rivers that the Dutch named the Varsche River. It was threaded by a double streamlet, with tiny bridges crossing at intervals and ran through the town centre providing the continuity of the axis of the Company’s Garden linked by way of an old gateway, lined with stoeped townhouses of the burghers and at its foot was the wooden jetty. By 1767 the street had been widened into a fashionable promenade. It was described by a traveller in 1778 as “the most beautiful street or canal, bordered with oaks, along which are built the finest houses.”

HEERENGRACHT - what is today ADDERLEY STREET, circa 1832.

In the Platterklip Stream, what was once a riverbed is now a clearing in the trees, where a circle of rocks lie. This is where the slaves (and later the Washerwomen) took the population’s laundry. Here lies a gem of our cultural history...

Cape tradition was that the slaves took the population’s laundry to Platteklip. After the emancipation of the slaves (1 December 1834), their descendants continued to launder at Platteklip and at Capel Sluit, and to hold the 'place' as sacred.

“Every afternoon when the weather was warm the old washer-women would offload their bundles of washing at the corner of the Old Homestead at Oranjezicht. One of the sights of Table Mountain was the long procession of Malay washer-women, huge bundles on their heads, swinging along up Hope and Buitenkant Streets and along the Slave Walk. (Today’s Gorge Road) For many years they used the stream and rocks provided by nature, to be scoured and bleached. Almost daily more than 100 slaves could be seen, busy with the family washing.

After the abolition of slavery, there was a celebration along Platteklip on the first of December each year. The washer-women would clutter up the mountain in their ‘kaperrangs’ (clogs). Early in the afternoon they would leave their washing and dance waltzes to improvised music. Then, as twilight began to creep through the pines, they would march with their bundles down the path by the crumbling slaves walls of the Oranjezicht and Rheezicht estates.”

On one such occasion, an attractive Malay girl, the wife of an Hafiz, named Abdul Malik, lost the ring her husband sometimes let her wear, while washing clothes at Platteklip Gorge. She and her friends searched high and low along the banks, but the ring was never found again......

The ring had been given to Abdul by a great scholar in Mecca under whom Abdul studied Islam. The aged scholar considered him to be his best scholar; and besides bestowing much love upon him, gave him a ring which he was always to wear on his finger. The significance of the ring was never understood, until one day when he went to have his head shaved according to Islamic rule. The barber found that the razor would not cut. After attempts with a second razor had also failed, someone in the shop suggested that Abdul might be wearing a charm, guaranteed to prevent his being harmed by a knife. Puzzled, Abdul removed the ring and experienced no difficulty being shaved. On occasions, the Hafiz’s wife found that when she was wearing the ring, she was unable to cut bread and anything with a blade seemed to be magically turned away when brought near her.

The ring was lost. The search was fruitless. Tradition says that the Hafiz’s magic ring will be found again, one day.” --In Joe Lison, unpublished manuscript "From Rivulets to Reservoirs", 1970:38-39.

“Every afternoon when the weather was warm the old washer-women would offload their bundles of washing at the corner of the Old Homestead at Oranjezicht. One of the sights of Table Mountain was the long procession of Malay washer-women, huge bundles on their heads, swinging along up Hope and Buitenkant Streets and along the Slave Walk. (Today’s Gorge Road) For many years they used the stream and rocks provided by nature, to be scoured and bleached. Almost daily more than 100 slaves could be seen, busy with the family washing.

After the abolition of slavery, there was a celebration along Platteklip on the first of December each year. The washer-women would clutter up the mountain in their ‘kaperrangs’ (clogs). Early in the afternoon they would leave their washing and dance waltzes to improvised music. Then, as twilight began to creep through the pines, they would march with their bundles down the path by the crumbling slaves walls of the Oranjezicht and Rheezicht estates.”

On one such occasion, an attractive Malay girl, the wife of an Hafiz, named Abdul Malik, lost the ring her husband sometimes let her wear, while washing clothes at Platteklip Gorge. She and her friends searched high and low along the banks, but the ring was never found again......

The ring had been given to Abdul by a great scholar in Mecca under whom Abdul studied Islam. The aged scholar considered him to be his best scholar; and besides bestowing much love upon him, gave him a ring which he was always to wear on his finger. The significance of the ring was never understood, until one day when he went to have his head shaved according to Islamic rule. The barber found that the razor would not cut. After attempts with a second razor had also failed, someone in the shop suggested that Abdul might be wearing a charm, guaranteed to prevent his being harmed by a knife. Puzzled, Abdul removed the ring and experienced no difficulty being shaved. On occasions, the Hafiz’s wife found that when she was wearing the ring, she was unable to cut bread and anything with a blade seemed to be magically turned away when brought near her.

The ring was lost. The search was fruitless. Tradition says that the Hafiz’s magic ring will be found again, one day.” --In Joe Lison, unpublished manuscript "From Rivulets to Reservoirs", 1970:38-39.

A ring was found in 2006, by an American scholar - Dr. Elizabeth Grzymala-Jordan, on this site. The dig revealed plentiful artefacts - enough to fill 34 apple boxes. Dr. Grzymala-Jordan's work looked at slavery globally, and in particular at the role of women slaves. More specifically, the work she did in Cape Town, is recorded in a document submitted as part of her DPhil in Anthropology: "FROM TIME IMMEMORIAL: Washerwomen, Culture, and Community in Cape Town, South Africa", January 2006 - submitted to the Graduate School New Brunswick, State University of New Jersey.

Robert Ernest Bryson (born 1867, Glasgow) was a composer who wrote symphonies. In 1926 he composed an opera: "The Leper’s Flute", with words by Ian Colvin. The story is set at the site of the Platteklip Waterfall and washing pools. A copy of the opera can be found here.

WATER POLLUTED

A poem by Willian Bridekirk, published in May 1825, describes:

A poem by Willian Bridekirk, published in May 1825, describes:

“Canals, thro’ some of the streets flow.

Which stink confoundly you must know;

And serve so handy for lazy wenches,

To cast therein their slop-pail stenches.

Some sluts, besides the above named slop,

Other burdens have been known to drop

Into these reservoirs of pollution”.

Which stink confoundly you must know;

And serve so handy for lazy wenches,

To cast therein their slop-pail stenches.

Some sluts, besides the above named slop,

Other burdens have been known to drop

Into these reservoirs of pollution”.

The ‘grachte’ had become the dumping place for the town’s rubbish. By the time the Bubonic Plague hit Cape Town, Water was forced underground and became redundant, making its way to the sea via sewers and stormwater channels.

A systematic programme of arching over and enclosing the canals was initiated in 1838, directly changing the character of old Cape Town. At first a number of bridges were built over the canals and some canals paved. Eventually the majority of the grachte had been replaced by brick sewers. By the end of the 1860s, the last stretch of the Heerengracht had been covered and the street, renamed Adderley Street. In 1901, the last of the open Water courses was closed, in District Six.

A systematic programme of arching over and enclosing the canals was initiated in 1838, directly changing the character of old Cape Town. At first a number of bridges were built over the canals and some canals paved. Eventually the majority of the grachte had been replaced by brick sewers. By the end of the 1860s, the last stretch of the Heerengracht had been covered and the street, renamed Adderley Street. In 1901, the last of the open Water courses was closed, in District Six.

WATER LINKS PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

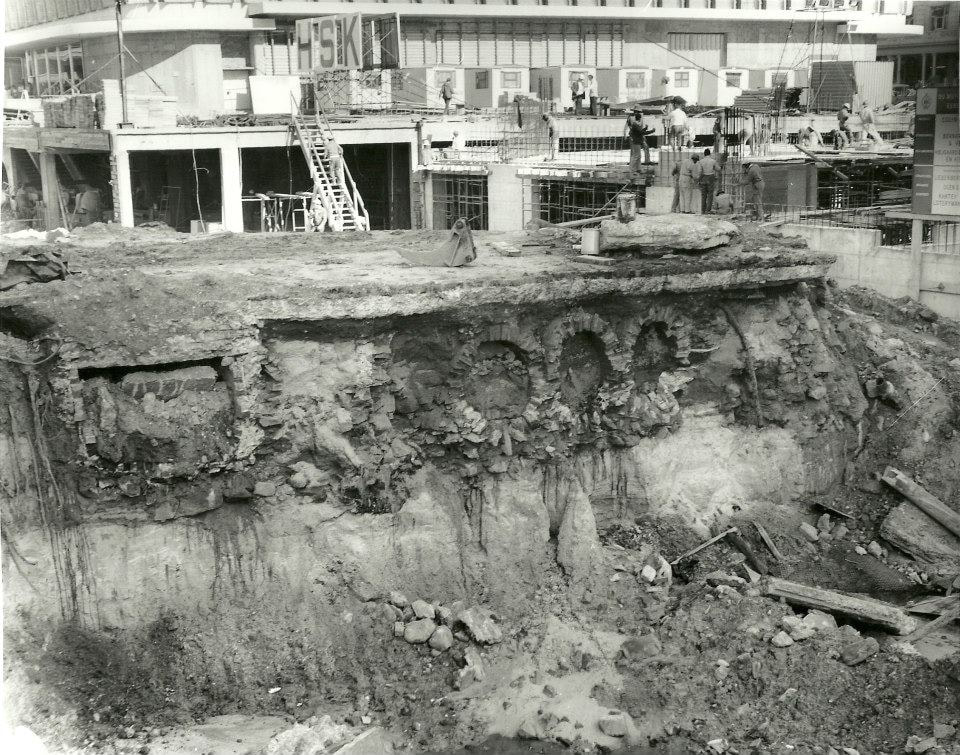

The Golden Acre Shopping Mall was constructed on the original shoreline, the previous frontier between the city and the sea, at the very spot where the colonialists and slaves disembarked. In the 1970s excavations revealed the earliest dam and sluice that was built to supply the passing trade.

The Golden Acre Shopping Mall was constructed on the original shoreline, the previous frontier between the city and the sea, at the very spot where the colonialists and slaves disembarked. In the 1970s excavations revealed the earliest dam and sluice that was built to supply the passing trade.

Subterranean sluice channels uncovered during the building of the Golden Acre shopping mall, c. 1973/4.

Excavations of the Cape Town train station forecourt for the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, revealed the timber from the original old wooden jetty of the early 1600s; an old ship's anchor and a British well, which was quickly and deliberately covered.

The missed opportunity to reveal the ancient entrance to the city by sea faring nations where South Africa’s colonists and slave ancestors landed, represented a closing of a frontier at a time when so many eyes were focused on the city. In the rush to complete construction before the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, the site was backfilled and covered over. In the words of Archaeologist, Dr. Antonia Malan: "It was here that sea voyagers stepped ashore - whether freely or not, healthy or sick or dying - it was the umbilical cord that sustained passing ships with fresh food and water - and conducted vital supplies to the struggling settlement - from where indigenous and foreign exiles and convicts were offloaded and shipped to Robben Island - where famous and infamous travellers disembarked.”

The missed opportunity to reveal the ancient entrance to the city by sea faring nations where South Africa’s colonists and slave ancestors landed, represented a closing of a frontier at a time when so many eyes were focused on the city. In the rush to complete construction before the FIFA 2010 Football World Cup, the site was backfilled and covered over. In the words of Archaeologist, Dr. Antonia Malan: "It was here that sea voyagers stepped ashore - whether freely or not, healthy or sick or dying - it was the umbilical cord that sustained passing ships with fresh food and water - and conducted vital supplies to the struggling settlement - from where indigenous and foreign exiles and convicts were offloaded and shipped to Robben Island - where famous and infamous travellers disembarked.”

Journeying through the ‘lost spaces’ associated with Cape Town’s waterways, a global story of Water, land and humankind unfolds. When one uncovers the history of a 'place', it is through means of title deeds - ownership and power, however, when one uncovers the history of a 'place', through its Water - one uncovers the popular history of that place. As one follows the path of these waters from mountain to ocean, the fact that Water follows the path of least resistance and has no boundaries, is revealed.

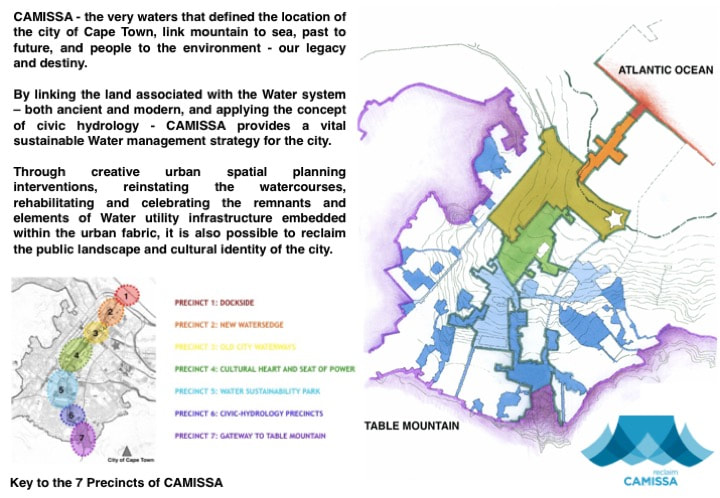

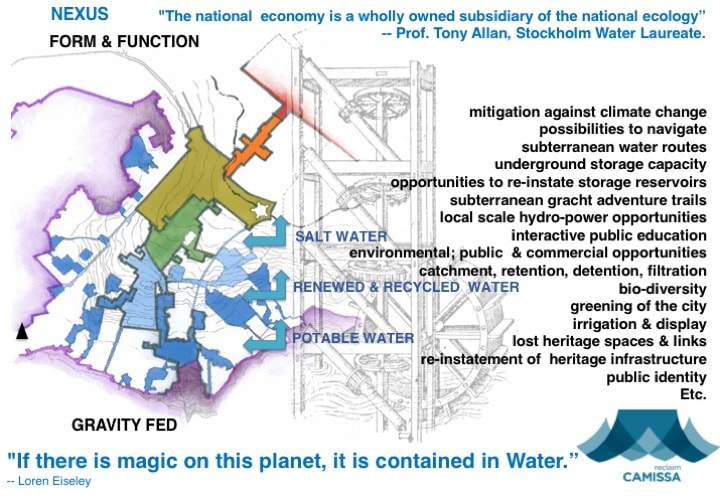

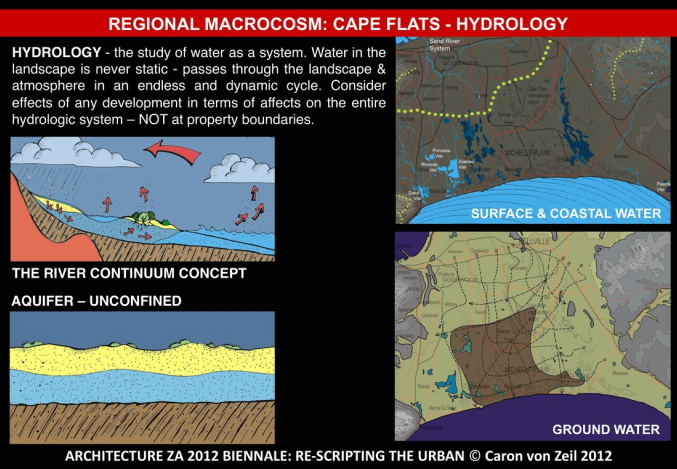

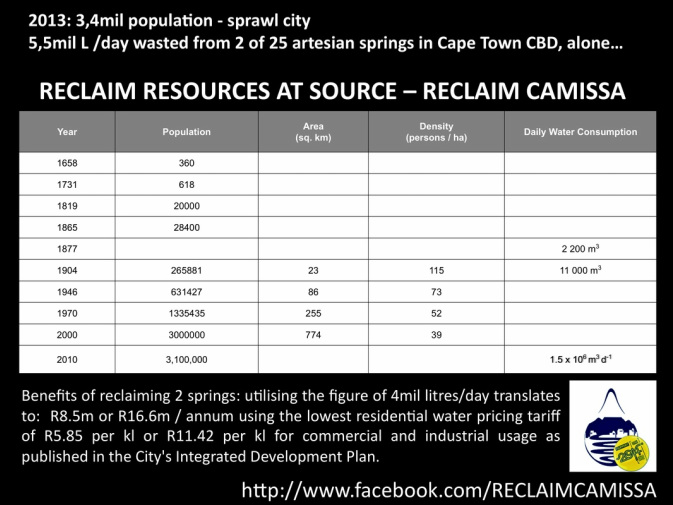

CAMISSA is a (hydro-spatial) development framework, which through the use of Water, focuses on the re-instatement of the socio-ecological link that reunites the mountain and the sea, into a public landscape - as a sustainable solution for Cape Town's CBD.

This framework is comprised of a series of systematic structural maps for the integration of natural and urban layers of the city. It is a system that re-structures the city according to environmental principles and establishes integrated and flexible urban development around the natural resource of Water. Thus, enabling us to rise and meet future environmental challenges in a city no longer Water secure. The vision is one of a Water Sensitive City and a genuinely progressive Water management strategy that offers opportunities for new models to transform the future wellbeing of the city into an equal society for all people; whilst allowing for public integration and education through the recreational use of the system.

This framework is comprised of a series of systematic structural maps for the integration of natural and urban layers of the city. It is a system that re-structures the city according to environmental principles and establishes integrated and flexible urban development around the natural resource of Water. Thus, enabling us to rise and meet future environmental challenges in a city no longer Water secure. The vision is one of a Water Sensitive City and a genuinely progressive Water management strategy that offers opportunities for new models to transform the future wellbeing of the city into an equal society for all people; whilst allowing for public integration and education through the recreational use of the system.

What is evident, after much research and analysis is that there are seven distinct areas within this catchment that reflect the fundamental reason for the city's establishment - the ways in which Water occurs, previously functioned; and could potentially function in the future - if environmental principles are applied; and if we are to reclaim and use the Water resources and their associated land parcels - to the benefit of the city and her inhabitants, optimally.

These "precincts" have been defined after spatially mapping the geographical area from the perspective of 'a city within its region'; and this local area within its metropolitan context - in accordance with its natural and urban systems; and then overlayed with a series of maps that examine how the city functions on a temporal and spatial basis, throughout the different seasons of Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn - day or night.

The seven precincts (more like the French term “quartier”) are geographical areas, which unlock the potential to design a sequence of projects, which can be rolled out systematically; and which capture the full range of historical, cultural, social and ecological heritage; and provide economic, educational and place-making potentials associated with the city's Water resource - in a holistic, integrated and co-ordinated manner.

Today, Cape Town is Water challenged: chronic shortages coupled with extreme Water pollution. Restrictions on Water usage are currently legislated. Tomorrow will bring the additional realities of climate change: rising sea levels and periods of alternating flooding and drought. Water-related issues are a priority, not only because future economic growth relies on adequate provision of Water that will sustain development for present and future generations – but life itself.

Many of the sites encompassed in these precincts are testimony to our primal need for Water, to the interaction between our predecessors and our interaction with the Earth, and our imperative need to co-exist respectfully and harmoniously with nature. It is thus crucial that they are protected that we may benefit from them in the future. As the environmental crisis escalates worldwide, urgent and thoughtful steps need to be taken to reduce Water loss, waste and pollution. Strengthened community awareness and participation, collaborative approaches and an empowered citizenry are evermore essential - to rekindle our profound connection and respect for Water.

What is evident, after much research and analysis is that there are seven distinct areas within this catchment that reflect the fundamental reason for the city's establishment - the ways in which Water occurs, previously functioned; and could potentially function in the future - if environmental principles are applied; and if we are to reclaim and use the Water resources and their associated land parcels - to the benefit of the city and her inhabitants, optimally.

These "precincts" have been defined after spatially mapping the geographical area from the perspective of 'a city within its region'; and this local area within its metropolitan context - in accordance with its natural and urban systems; and then overlayed with a series of maps that examine how the city functions on a temporal and spatial basis, throughout the different seasons of Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn - day or night.

The seven precincts (more like the French term “quartier”) are geographical areas, which unlock the potential to design a sequence of projects, which can be rolled out systematically; and which capture the full range of historical, cultural, social and ecological heritage; and provide economic, educational and place-making potentials associated with the city's Water resource - in a holistic, integrated and co-ordinated manner.

Today, Cape Town is Water challenged: chronic shortages coupled with extreme Water pollution. Restrictions on Water usage are currently legislated. Tomorrow will bring the additional realities of climate change: rising sea levels and periods of alternating flooding and drought. Water-related issues are a priority, not only because future economic growth relies on adequate provision of Water that will sustain development for present and future generations – but life itself.

Many of the sites encompassed in these precincts are testimony to our primal need for Water, to the interaction between our predecessors and our interaction with the Earth, and our imperative need to co-exist respectfully and harmoniously with nature. It is thus crucial that they are protected that we may benefit from them in the future. As the environmental crisis escalates worldwide, urgent and thoughtful steps need to be taken to reduce Water loss, waste and pollution. Strengthened community awareness and participation, collaborative approaches and an empowered citizenry are evermore essential - to rekindle our profound connection and respect for Water.

Legacy and Destiny

Water carriers , Indlovini, Monwabisi - Cape Town.

Photo credit: Caron von Zeil.

Water carriers , Indlovini, Monwabisi - Cape Town.

Photo credit: Caron von Zeil.

So, perhaps on this Heritage Day, you may wish to contemplate our ecological and social heritage, and take a stroll along CAMISSA with this guided map - although it is much in need of an update.

ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED by THE RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed