This blogpost, first published in 2014, has since been added to, to include issues around Water and Urbanisation; Water Security; and groundwater - given the Water crisis facing Cape Town.

It is a long, but hopefully informative post.

It is a long, but hopefully informative post.

'every drop counts'

WATER & URBANISATION

More than 50% of the world's population currently live in areas, occupying 2% of the world’s land surface, and consuming 75% of natural resources. As the world becomes increasingly urbanised, there comes a host of challenges. Experts believe that by 2030, 90% of urban growth, will occur in developing countries, with 80% of the global urban population in the towns and cities of Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is said, that 62% of Africa will be urbanised. (GWP)

This unprecedented rate of urban growth represents a unique opportunity to build more sustainable, innovative and equitable towns and cities. Without expanding on the urban environmental discourse, let us agree that 'Cities are well-placed to play a major role in decoupling economic development from resource use and environmental impacts, while finding a better balance between social, environmental and economic objectives. And that resource-efficient cities combine greater productivity and innovation with lower costs and reduced environmental impacts, offering at the same time financial savings and increased sustainability.'

This unprecedented rate of urban growth represents a unique opportunity to build more sustainable, innovative and equitable towns and cities. Without expanding on the urban environmental discourse, let us agree that 'Cities are well-placed to play a major role in decoupling economic development from resource use and environmental impacts, while finding a better balance between social, environmental and economic objectives. And that resource-efficient cities combine greater productivity and innovation with lower costs and reduced environmental impacts, offering at the same time financial savings and increased sustainability.'

"Cities are human creations and so are shaped according to the principles and approaches that our societies are founded upon. In order to build more resource-efficient cities, a change to global thinking on urbanisation is needed."

-- Achim Steiner, Executive Director, UNEP 2013.

It becomes apparent that at a global level, Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) is fundamental to the global development agenda. Integrated Urban Water Resource Management (IUWM) requires a complex integration of disciplines and scales of function, in order for a city to be Water secure in the future, but what is Cape Town doing to ensure that the crucial link to Water security is achieved within the focus areas of climate change, food security, urbanisation, energy, ecosystems and population growth?

Precedent for solutions is already well on its way...

"By 2030, Africa’s urban population will double, and the difficulties African cities currently face in providing sustainable Water services will be exacerbated". "The Future of Water in African Cities: Why Waste Water?" argues that the traditional approach of one source, one system, and one discharge cannot close the Water gap. A more integrated, sustainable, and flexible approach, which takes into account new concepts such as 'Water fit to a purpose', is needed in African cities. This study provides examples of cities in Africa and beyond that have already implemented Integrated Urban Water Resource Management (IUWM) approaches both in terms of technical and institutional solutions."

Precedent for solutions is already well on its way...

"By 2030, Africa’s urban population will double, and the difficulties African cities currently face in providing sustainable Water services will be exacerbated". "The Future of Water in African Cities: Why Waste Water?" argues that the traditional approach of one source, one system, and one discharge cannot close the Water gap. A more integrated, sustainable, and flexible approach, which takes into account new concepts such as 'Water fit to a purpose', is needed in African cities. This study provides examples of cities in Africa and beyond that have already implemented Integrated Urban Water Resource Management (IUWM) approaches both in terms of technical and institutional solutions."

WHAT IS WATER SECURITY?

"The capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities of acceptable quality Water for sustaining livelihoods, human well-being, and socio-economic development, for ensuring protection against Water-borne pollution and Water-related disasters, and for preserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political stability." --UN-Water, 2013.

"80% of the world's population faces high-level Water security or Water-related bio-diversity risk". - Karen Bakker, 2012. |

According to the UN-Water Analytical Brief on Water Security and the Global Water Agenda, 2013 'Water security encapsulates complex and interconnected challenges, and highlights Water’s centrality for achieving a larger sense of security, sustainability, development and human well-being. Many factors contribute to Water security, ranging from biophysical to infrastructural, institutional, political, social and financial matters – many of which lie outside the Water realm. In this respect, Water security lies at the centre of many security areas, each of which is intricately linked to Water. Addressing this goal therefore requires interdisciplinary collaboration across sectors, communities and political borders'.

--The United Nations University: "Water Security and the Global Water Agenda", 2013.

In the article by Karen Bakker: "Water Security: Research Challenges and Opportunities", Water security is defined as an “acceptable level of Water-related risks to humans and ecosystems, coupled with the availability of Water of sufficient quantity and quality to support livelihoods, national security, human health, and ecosystem services”. The author highlights the main challenge of balancing human and environmental needs, whilst protecting essential ecosystem services and biodiversity - as problems, largely due to a lack of

i) conceptual common ground for effective Water management and policy-making across disciplines and sectors;

ii) sufficient interdisciplinary collaboration and institutional incentives; and

iii) a discipline and/or scale mismatch - i.e. where certain disciplines focus on different scales, for example hydrologists focus on the catchment (watershed), but politicians focus on the nation.

The Global Water Partnership (GWP) launched a new 2014 - 2019 global strategy towards a Water secure world, which was developed through a year-long process of regional dialogues and consultations with their growing network of over 2,900 partner organizations across 172 countries. The strategy "Towards 2020" stresses the need for "innovative and multi-sectoral approaches to adequately address the manifold threats and opportunities relating to sustainable Water resource management in the context of climate change, rapid urbanisation, and growing inequalities”.

--The United Nations University: "Water Security and the Global Water Agenda", 2013.

In the article by Karen Bakker: "Water Security: Research Challenges and Opportunities", Water security is defined as an “acceptable level of Water-related risks to humans and ecosystems, coupled with the availability of Water of sufficient quantity and quality to support livelihoods, national security, human health, and ecosystem services”. The author highlights the main challenge of balancing human and environmental needs, whilst protecting essential ecosystem services and biodiversity - as problems, largely due to a lack of

i) conceptual common ground for effective Water management and policy-making across disciplines and sectors;

ii) sufficient interdisciplinary collaboration and institutional incentives; and

iii) a discipline and/or scale mismatch - i.e. where certain disciplines focus on different scales, for example hydrologists focus on the catchment (watershed), but politicians focus on the nation.

The Global Water Partnership (GWP) launched a new 2014 - 2019 global strategy towards a Water secure world, which was developed through a year-long process of regional dialogues and consultations with their growing network of over 2,900 partner organizations across 172 countries. The strategy "Towards 2020" stresses the need for "innovative and multi-sectoral approaches to adequately address the manifold threats and opportunities relating to sustainable Water resource management in the context of climate change, rapid urbanisation, and growing inequalities”.

WATER SECURITY IN CAPE TOWN

Water security is a major constraining factor in the future economic growth of Cape Town; and the South Western Cape in particular is critically exposed to Water scarcity issues within the next decade. In 2017 severe restrictions commenced, as demand was soon to outstrip supply, during 2018 - some say 2019, now.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND - QUANTITY

Cape Town’s Water supply is mostly pumped and piped from the food growing region - from mountain rivers and streams in the surrounding Drakenstein and Franschhoek mountains. The primary source comes from Theewaterskloof Dam, supplemented by Steenbras upper and lower dams; Wemmershoek Dam; Voelvlei Dam; Berg River Dam - which make up 20% of the supply; and the five Table Mountain dams, including Woodhead Dam. http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/Pages/CapeTownsWaterSupplyBoosted.aspx

SUPPLY AND DEMAND - QUANTITY

Cape Town’s Water supply is mostly pumped and piped from the food growing region - from mountain rivers and streams in the surrounding Drakenstein and Franschhoek mountains. The primary source comes from Theewaterskloof Dam, supplemented by Steenbras upper and lower dams; Wemmershoek Dam; Voelvlei Dam; Berg River Dam - which make up 20% of the supply; and the five Table Mountain dams, including Woodhead Dam. http://www.capetown.gov.za/en/Pages/CapeTownsWaterSupplyBoosted.aspx

Cape Town's Water supply system is a complex, inter-linked system of dams; pipelines; tunnels and distribution networks. Some elements of the system are owned and operated by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry and some by the City of Cape Town. According to the City of Cape Town's Water Services Directorate, it is "the largest vertically integrated Water utility in South Africa, serving the largest number of connections (approximately 590 000 formal erven and approximately 100 000 informal sites), with a total annual consumption of potable Water of approximately 300million Kls; and annual wastewater treatment - close to 193million Kls."

Future developments of the Cape Town Water Supply indicate "that demand in the area served by the system will exceed supply by 2019, and possibly even earlier if Water availability diminishes because of climate change and if Water conservation measures in Cape Town should not be as successful as envisaged. A number of additions to the system, such as the heightening of dams, are considered as well as seawater desalination in order to cope with the rising demand." -- as published by the City of Cape Town, in 2014.

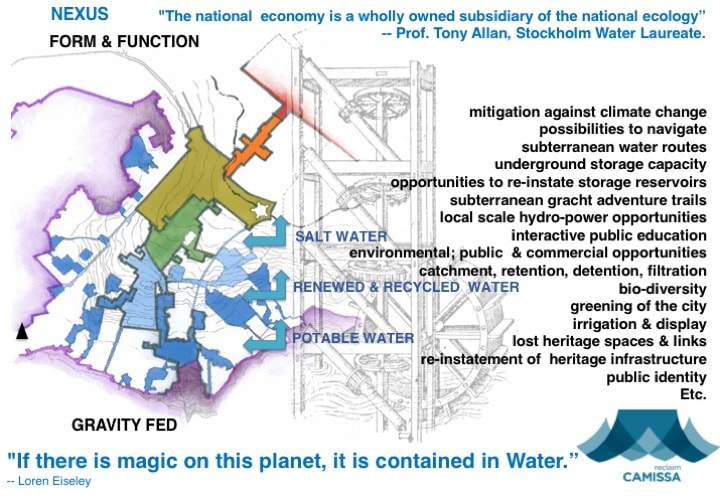

However, bulk supply is not the answer, and given the lessons learned during the Californian drought, and other climate change impacts on cities - 20th Century infrastructure is not going to suffice during the 21st Century. Diverse, de-centralised solutions are suggested, and this starts with the mapping and monitoring of our sources: stormwater management, sewage recycling, rainwater harvesting, fog harvesting, groundwater (aquifer) protection, recharge and usage, rivers, streams, vleis, beaches, etc. It is necessary that we examine our city within its regional hydro-spatial capacity, and observe the principle:

"WATER FIRST", due to Water’s centrality for achieving a larger sense of security, sustainability, and human well-being, when considering any development.

The need is to -

1) research, map and define our Watersheds;

2) design Metropolitan scale Hydro-Spatial Frameworks, accordingly;

3) design Hydro-Spatial Development Frameworks at the Sub-Metropolitan scale;

4) to establish Catchment Agencies; and

5) to establish Community Water Stewardship Councils - in this way affect Behavioural Change and Social Transformation, as "when the source of Water is local, known and honoured culturally, people understand the importance of Water to their health and thus, they care for this source." -- Betsy Damon, Keepers of the Waters.

NON-REVENUE WATER

Research by the Water Research Commission indicates that nationally, 36.8% of potable Water destined for urban areas has been lost over the past six years due to leaks; failing infrastructure; and poor financial controls by local authorities - amongst other reasons. This amounts to 1 580 million cubic metres of Water a year, valued at R11billion. According to Xanthea Limberg of the CoCT, Cape Town has an average loss of 17%, which is not bad considering that a 'World Class City', would average around 12%. Whilst measures are being introduced to reduce this loss, it would seem that what is largely being ignored, is the obvious - to satisfy Water needs closer to source, i.e. within geographic proximity of consumption; together with better management of such catchment areas, thereby reducing infrastructural expansion and maintenance.

However, it would seem that expert advice and strategy pertaining to groundwater or green-frasture and/or eco-system services is ignored. CoCT: Water Services Development Plan, WSDP 2012-2013.

Future developments of the Cape Town Water Supply indicate "that demand in the area served by the system will exceed supply by 2019, and possibly even earlier if Water availability diminishes because of climate change and if Water conservation measures in Cape Town should not be as successful as envisaged. A number of additions to the system, such as the heightening of dams, are considered as well as seawater desalination in order to cope with the rising demand." -- as published by the City of Cape Town, in 2014.

However, bulk supply is not the answer, and given the lessons learned during the Californian drought, and other climate change impacts on cities - 20th Century infrastructure is not going to suffice during the 21st Century. Diverse, de-centralised solutions are suggested, and this starts with the mapping and monitoring of our sources: stormwater management, sewage recycling, rainwater harvesting, fog harvesting, groundwater (aquifer) protection, recharge and usage, rivers, streams, vleis, beaches, etc. It is necessary that we examine our city within its regional hydro-spatial capacity, and observe the principle:

"WATER FIRST", due to Water’s centrality for achieving a larger sense of security, sustainability, and human well-being, when considering any development.

The need is to -

1) research, map and define our Watersheds;

2) design Metropolitan scale Hydro-Spatial Frameworks, accordingly;

3) design Hydro-Spatial Development Frameworks at the Sub-Metropolitan scale;

4) to establish Catchment Agencies; and

5) to establish Community Water Stewardship Councils - in this way affect Behavioural Change and Social Transformation, as "when the source of Water is local, known and honoured culturally, people understand the importance of Water to their health and thus, they care for this source." -- Betsy Damon, Keepers of the Waters.

NON-REVENUE WATER

Research by the Water Research Commission indicates that nationally, 36.8% of potable Water destined for urban areas has been lost over the past six years due to leaks; failing infrastructure; and poor financial controls by local authorities - amongst other reasons. This amounts to 1 580 million cubic metres of Water a year, valued at R11billion. According to Xanthea Limberg of the CoCT, Cape Town has an average loss of 17%, which is not bad considering that a 'World Class City', would average around 12%. Whilst measures are being introduced to reduce this loss, it would seem that what is largely being ignored, is the obvious - to satisfy Water needs closer to source, i.e. within geographic proximity of consumption; together with better management of such catchment areas, thereby reducing infrastructural expansion and maintenance.

However, it would seem that expert advice and strategy pertaining to groundwater or green-frasture and/or eco-system services is ignored. CoCT: Water Services Development Plan, WSDP 2012-2013.

The problem in the Western Cape, is one of HYDROCIDE - a term coined by Jan Lundqvist (1998), meaning simply when a society suffers as a result of the social misuse of their Water resources.

“that area of land,

a bounded hydrologic system,

within which all living things

are inextricably linked

by their common Water course

and where, as humans settled,

simple logic demanded that

they become part of a community” --John Wesley Powell

Cape Town requires to make the shift towards a Water Sensitive City: "A city in which Water is managed with regard for its rural origins, coastal destinations and social/cultural significance becomes a Water Sensitive City. A philosophy of flexibility in supply and use to meet all users’ needs underpins the collection and movement of Water, and the technologies to facilitate the physical movement of Water are designs that manifest these ideals visually for all to acknowledge and appreciate." - UNESCO-IHE

GROUNDWATER - A SUSTAINABLE RESOURCE, IF PROTECTED

Waterhof Spring, on the slopes of Table Mountain. Photo credit: Caron von Zeil.

"What makes the desert beautiful is that somewhere it hides a well." --Antoine de Saint-Exupery

"What makes the desert beautiful is that somewhere it hides a well." --Antoine de Saint-Exupery

There is approximately one hundred times more groundwater on Earth than fresh surface Water; and given the current environmental issues - climate change, Water and food scarcity - the protection of groundwater is vital.

"Why is groundwater so important? First, it’s generally a more reliable source of Water than surface Water, which is naturally protected from contamination. Second, groundwater acts as a natural buffer from drought, helping to smooth out rainfall patterns, thereby increasing resilience to climate change. Finally, it can generally be found close to the point of demand. It’s for these reasons and more that groundwater is the main source of Water in low-income countries."

International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

In "Unsustainable use of groundwater may threaten global food security", by Karen Villholth, Aditya Sood, and Evgeniya Anisimova, the authors point out that "groundwater constitutes 30% of all liquid freshwater on Earth" the importance of implementing measures to protect groundwater resources are thus evident.

"Why is groundwater so important? First, it’s generally a more reliable source of Water than surface Water, which is naturally protected from contamination. Second, groundwater acts as a natural buffer from drought, helping to smooth out rainfall patterns, thereby increasing resilience to climate change. Finally, it can generally be found close to the point of demand. It’s for these reasons and more that groundwater is the main source of Water in low-income countries."

International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

In "Unsustainable use of groundwater may threaten global food security", by Karen Villholth, Aditya Sood, and Evgeniya Anisimova, the authors point out that "groundwater constitutes 30% of all liquid freshwater on Earth" the importance of implementing measures to protect groundwater resources are thus evident.

GROUNDWATER

CAMISSA - THE CITY BOWL SPRINGS (TABLE VALLEY CATCHMENT AREA)

The occurrence of springs along the slopes of Table Mountain are due to the exposure of the contact zone between the porous Sandstone and the impermeable Granite.

The occurrence of springs along the slopes of Table Mountain are due to the exposure of the contact zone between the porous Sandstone and the impermeable Granite.

According to archival records there are thirty-six artesian springs in the City Bowl of Cape Town. Thirty-two have been located, of which only thirteen are listed by the municipality. Data regarding the flow dynamics - both quantitative and qualitative, have not been adequately recorded or monitored, since the late 1890s.

In 2015, an updated "Springs Strategy Report" was released. Given the current #WaterCrisis and having obtained two expert reviews of the document, we are of the opinion, that the report and strategy requires a review by an interdisciplinary team of experts.

This Water was not until recently utilised within the municipal Water supply; nor does the Water benefit the ecological system to support the city's biodiversity. Since August 2017, it seems that chlorinators have been installed along the walls of Molteno Reservoir, that appear to be filtering a portion of the supply - as can be seen in this video by Gerhard Söhnge. According to a letter by the Honourable Mayor, Patricia de Lille in the newspapers, 2million litres from the Stadtsfontein was diverted to Molteno Reservoir on 8 November 2017.

In 2015, an updated "Springs Strategy Report" was released. Given the current #WaterCrisis and having obtained two expert reviews of the document, we are of the opinion, that the report and strategy requires a review by an interdisciplinary team of experts.

This Water was not until recently utilised within the municipal Water supply; nor does the Water benefit the ecological system to support the city's biodiversity. Since August 2017, it seems that chlorinators have been installed along the walls of Molteno Reservoir, that appear to be filtering a portion of the supply - as can be seen in this video by Gerhard Söhnge. According to a letter by the Honourable Mayor, Patricia de Lille in the newspapers, 2million litres from the Stadtsfontein was diverted to Molteno Reservoir on 8 November 2017.

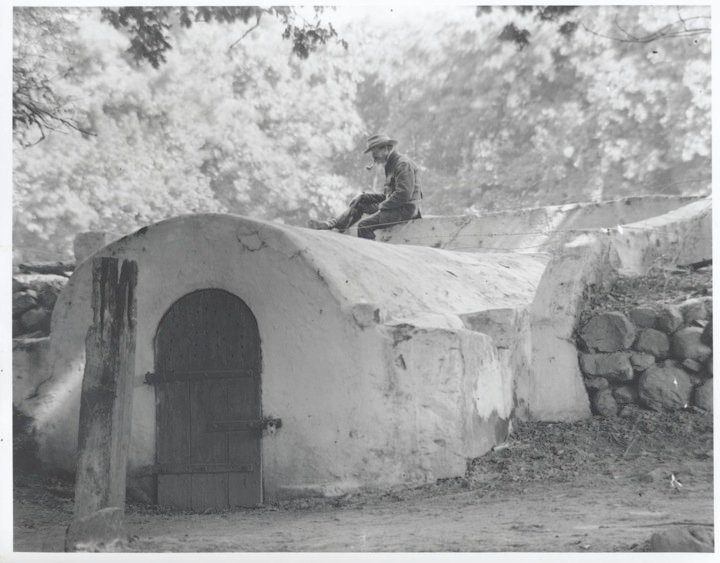

Stadtsfontein, photo credit: Caron von Zeil.

As a source of potable Water - groundwater plays an increasingly important role; and given the quantity available within the study area (almost 6million litres/day on a 3200m site) - the response by RECLAIM CAMISSA to a proposal for the ORANJEZICHT CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN (OCMP) is pertinent:

As part of a transparent public process of decision-making and aligned with our mandate 'to provide a stewardship for the waters that flow from Table Mountain to the Atlantic Ocean, that will reclaim Cape Town’s central city connection to the Water - ensuring that the public is able to enjoy the right to this Water; and that the Water remain in good ecological health' - we provide the following concerns, rationale and recommendations regarding the OCMP.

As part of a transparent public process of decision-making and aligned with our mandate 'to provide a stewardship for the waters that flow from Table Mountain to the Atlantic Ocean, that will reclaim Cape Town’s central city connection to the Water - ensuring that the public is able to enjoy the right to this Water; and that the Water remain in good ecological health' - we provide the following concerns, rationale and recommendations regarding the OCMP.

CONCERNS & RATIONALE

As the unseen nature of groundwater poses a daunting challenge in its quantity and quality - in order to secure the resource for optimal future use, it requires measures for protection, conservation and management that acknowledge the source as inseparable from its associated land; and contextual importance within its hydrological system, and the broader hydrological cycle.

Whilst in agreement that an incremental approach to conservation is a pragmatic one, it is problematic that the scope of the CoCT's brief for the OCMP did not include an investigation of the significance of the study area's Water resources within the hydrological landscape.

The OCMP thus ignores two vital factors:

1) the groundwater resource as integral to the site; and

2) the importance and significance of the site within the hydrological system of the Table Valley Catchment Area - in terms of the natural and cultural history of the city; and future Water security; or

3) the qualitative value of the site as an asset to the city in terms of both public environmental and cultural education.

As the unseen nature of groundwater poses a daunting challenge in its quantity and quality - in order to secure the resource for optimal future use, it requires measures for protection, conservation and management that acknowledge the source as inseparable from its associated land; and contextual importance within its hydrological system, and the broader hydrological cycle.

Whilst in agreement that an incremental approach to conservation is a pragmatic one, it is problematic that the scope of the CoCT's brief for the OCMP did not include an investigation of the significance of the study area's Water resources within the hydrological landscape.

The OCMP thus ignores two vital factors:

1) the groundwater resource as integral to the site; and

2) the importance and significance of the site within the hydrological system of the Table Valley Catchment Area - in terms of the natural and cultural history of the city; and future Water security; or

3) the qualitative value of the site as an asset to the city in terms of both public environmental and cultural education.

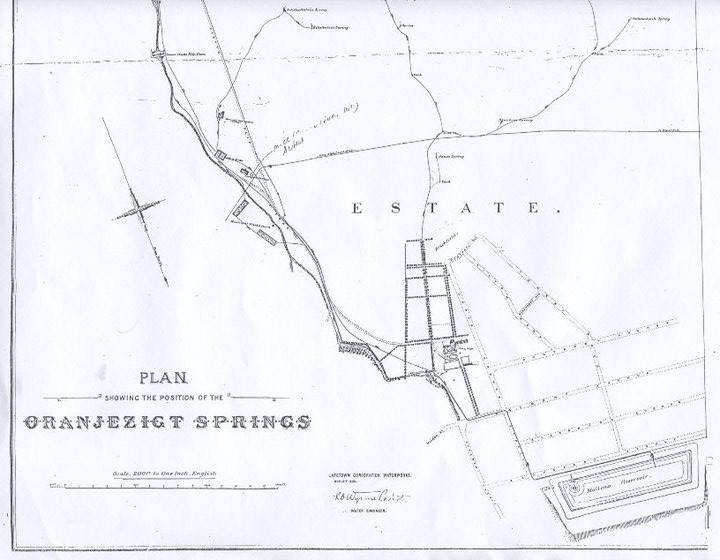

THE ORANJEZICHT SPRINGS MAP, by Cape Town Corporation Waterworks, November 1903.

Molteno Reservoir was once fed by Table Mountain's springs.

Molteno Reservoir was once fed by Table Mountain's springs.

WATER IN CAPE TOWN - PAST & FUTURE

Water is key to understanding and appreciating the natural and cultural history of the Mother City, it is after all, the very reason for settlement. Situated between two World Heritage Sites: Table Mountain and Robben Island - the hydrological system structured the city in the past. It is of unique ecological and cultural significance, and as the frontier of our modern state, it is a cultural landscape - where natural and cultural resources exist in relationship to their ecological contexts and reveal the human relationship with this land and Water over time. In the context of South Africa's socio-political history, this relationship is a tenuous one.

The study area is comprised of what remains of the former Oranjezicht Farmstead - once the largest farm in the Table Valley, confined by two tributaries and once containing twelve of the City Bowl’s springs. Five of these springs are (still) located in the ‘Field of Springs’ (Erf 861); portion Erf 858 - which contains a sub-system aquifer; and include the Stadtsfontein - quantitatively the largest yield (with an average of 2.77million litres per day) within the Table Valley Catchment Area. Due to the significant yield, the capture and processing thereof could provide a significant potential source of potable Water. The total available Water in this small area of 3200 square metres, is 5,987,520 litres of Water per day - as calculated in the Summer of 2012. Whilst 6million litres is only a small percentage of the total requirement of the city's dwellers, this would positively impact Water security. By accessing and utilising sources within close geographic proximity, it is possible to positively impact Water security in the Greater Cape Town Municipal Area (GCTMA); and assist in reduced risks and increased revenues with regard to Water supply management in the city as a whole. Such a project, would also set the necessary precedent of a move towards a Water Sensitive City.

THE STADTSFONTEIN - A NOTABLE NATURAL AND URBAN ELEMENT

For a brief history of the Stadtsfontein, click here.

Historically, Water from the Stadtsfontein was led down to the old shoreline to sustain global trade; and thus the spring gave rise to South Africa's first Environmental Law: Placcaat 12 of 1655: “Niet boven de stroom van de spruitjie daer de schepen haer Water halen te wassen en deselve troubel te maken”.

The study area is comprised of what remains of the former Oranjezicht Farmstead - once the largest farm in the Table Valley, confined by two tributaries and once containing twelve of the City Bowl’s springs. Five of these springs are (still) located in the ‘Field of Springs’ (Erf 861); portion Erf 858 - which contains a sub-system aquifer; and include the Stadtsfontein - quantitatively the largest yield (with an average of 2.77million litres per day) within the Table Valley Catchment Area. Due to the significant yield, the capture and processing thereof could provide a significant potential source of potable Water. The total available Water in this small area of 3200 square metres, is 5,987,520 litres of Water per day - as calculated in the Summer of 2012. Whilst 6million litres is only a small percentage of the total requirement of the city's dwellers, this would positively impact Water security. By accessing and utilising sources within close geographic proximity, it is possible to positively impact Water security in the Greater Cape Town Municipal Area (GCTMA); and assist in reduced risks and increased revenues with regard to Water supply management in the city as a whole. Such a project, would also set the necessary precedent of a move towards a Water Sensitive City.

THE STADTSFONTEIN - A NOTABLE NATURAL AND URBAN ELEMENT

For a brief history of the Stadtsfontein, click here.

Historically, Water from the Stadtsfontein was led down to the old shoreline to sustain global trade; and thus the spring gave rise to South Africa's first Environmental Law: Placcaat 12 of 1655: “Niet boven de stroom van de spruitjie daer de schepen haer Water halen te wassen en deselve troubel te maken”.

Stadtsfontein, as photographed by Arthur Elliot c1900 - Cape Archives E1971.

Given the significance of the Stadtsfontein, historically; and the potential of the groundwater available within the OCMA, there is necessity to protect and conserve the resource. This resource is evaluated, not only in terms of securing the Water available within the OCMA, but the potential economic impact of the hydrological system - in terms of the flux value of Water, which could potentially finance securing the ecological system as an authentic cultural landscape and thereby, enjoy tremendous economic impact from tourism.

The conservation and management of the resource, will need to address the challenging prospect of both the quantity and the quality thereof. The Field of Springs and its adjacent land, is an integral part of the spatial hydrological system, situated upstream and downstream from the springs of the Table Valley Catchment Area. It includes public land and private property, adjacent to both its surface and subterranean segments. The system could also provide spaces of leisure, learning, renewal and employment. The Water resource itself, provides a substantial self-sustaining economic opportunity, for the system as a whole.

RECLAIM CAMISSA's concerns with regard to the Water are focused on the need to protect and conserve the resource for future use by the public. For this purpose, the site requires investigation and evaluation in terms of the broader hydrological system, so that minimum setback distances around the groundwater resource together with development guideline standards to be established, that will offer basic protection for the resource.

The OCMA is integral to an internationally significant ecological and cultural system, to illustrate this, we provide the following rationale:

In terms of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NERA), the Stadtsfontein would have had continued protection, but it has been demoted from National Heritage Status.

On 4 October 2006, an application was made by the Oranjezicht Heritage Society to Heritage Western Cape with regard to a lease application for a portion on Erf no. 858, which was then a disused bowling green, upon which the Oranjezicht homestead once stood. The application included a motivation to have the land parcels (individual erven) consolidated into one single erf, so that a unified set of conservation guidelines could be applied for the sensitive treatment of the site.

The groundwater is integral to the site...

"Although the ultimate and comprehensive protection may not be a realistic goal, the concept of differentiated aquifer protection seems to indicate a more feasible option in achieving adequate protection qualitatively around different aquifer systems based on their classifications. This concept works on the premise that different aquifers due to their unique socio, economic and environmental importance require different levels of protection (Parsons and Conrad 1998). This protection may range from a simple generic setback distance (often referred to a minimum safe distance) around a water resource to a more complex mechanism of zoning. Source protection zoning seeks primarily to control land use activities, thus preventing or controlling pollution of groundwater resources. The method takes into account the concept of travel times and minimum safe distances to water supply and ensures that the time taken for the horizontal travel of the contaminant is sufficient to allow physical and biochemical degradation/dilution of the contaminant (DWAF 2008). The attenuation or elimination capacity of the sub-surface may in some cases reduce or completely eliminate the concentration of these contaminants via natural physical, chemical or biological processes.” -Yasmin Rajkumar and Yongxin Xu (2011)

Land use change on portion of Erf no. 858 (the former bowling green)

When the gardening lease from the CoCT was awarded to the Oranjezicht City Farm (OZCF), there was no Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, which should have been triggered by a change of land use in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NERA) and the Environment Conservation Act 73 0f 1989. In the development of the OCMP, it appears that the current land use (agriculture) has become acceptable. Whilst RECLAIM CAMISSA strongly support the concept of urban agriculture; and we commend the OZCF for having created a flourishing farm, and a powerful means by which to build community; and for making good use of previously fallow land - agriculture is not appropriate on the current land (portion of Erf No. 858). It is illegal in terms of both the The National Water Act, 1998 (NWA) and the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (NEMA) to allow agriculture - a pollutant of water, over a major water source.

The current OZCF project has destroyed artefacts of heritage significance without approval from heritage agencies. (e.g. The rocks lining the old watersloot have been removed and sloot is now planted with tress). And although we focus our concerns on the water issues with regard to the protection and conservation of the site; at some later stage would like to engage directly with other stakeholders and/or institutions with regard to the establishment of an inventory of other items on site; and research material that would contribute to more fully inclusive narrative of the farm.

QUANTITY & QUALITY

Flow data collected in late February, 2013 reflects that four springs collecting within the field, issue an average of 5,987,520 litres of Water per day in late Summer. A limited quantity of this Water is utilised at the Green Point Eco Park, the balance flows out to sea - wasted through the tunnels under the city's streets.

Water economics specific to the Field of Springs

As a case study, Reclaim Camissa’s PGWC110%GREEN Flagship Project: “The Field of Springs” proposed the capture and use of 6million litres of groundwater / day. The intent for the project, was to:

At a quantum level - the project sets the precedent, whereby similar projects could be rolled out in other areas of the GCTMA.

The benefits of reclaiming and processing this water:

By capturing potable Water at source for domestic and or commercial use the city would be enabled to embark on a project that satisfies Water needs, geographically closer to source. The resultant reduction in infrastructural expansion; maintenance and simultaneous reduction in loss of non-revenue Water (nationally 38.6%); the savings in energy to pump the equivalent quantity of Water from the Overberg; and disaster risk management strategies necessitated by Water catchment management areas that are geographically remote from the point of consumption - would translate into a reduced treatment and supply cost per kl compared with conventional current water supply strategies.

It is envisaged that once the water from the 5 springs in the Field of Springs is captured, and processed for use as part of the city’s potable Water supply, revenue generated through the sale of the Water would provide a (self-sustaining) financial opportunity to reclaim and develop future Water conservation precinct areas that are integral to the hydrological system; and for the management and operation of the system as a whole. In addition, a small portion of this Water sold via a green economy enterprise, such as a bicycle brigade to distribute Water for offices and restaurants; that free spring Water drinking fountains as way finders and public artworks, would display the city's Water, past and future - throughout the CBD.

The direct benefits from reclaiming and processing 4million litres/day - thereby retaining 2million litres/day for the ecological reserve, translates to:

1. *R8.5m or *R16.6m per annum revenue income, using the lowest residential water pricing tariff of *R5.85 per kl or *R11.42 per kl for commercial and industrial usage, as published in the City's Integrated Development Plan. (*as calculated in 2014)

2. The Water captured at this site equates to the free basic Water supply (as prior to restrictions) of 20,277 homes, without impact on the Water resources, as this is Water not currently captured. As such the project benefits the wider Cape Town community notwithstanding its geographic positioning within an affluent suburb and reduces demand and supply pressure. It should be noted that on 8 November 2017, the CoCT published the augmentation of 2million litres of Water / day, to Molteno Reservoir - as calculated in 2014.

3. Due to the elevation at which these springs issue, the Water/Energy nexus potential, with 4.5KW measured on Erf. 861, could result in the power needs required by the study area, to be produced on site via local, small scale hydro-power.

The conservation and management of the resource, will need to address the challenging prospect of both the quantity and the quality thereof. The Field of Springs and its adjacent land, is an integral part of the spatial hydrological system, situated upstream and downstream from the springs of the Table Valley Catchment Area. It includes public land and private property, adjacent to both its surface and subterranean segments. The system could also provide spaces of leisure, learning, renewal and employment. The Water resource itself, provides a substantial self-sustaining economic opportunity, for the system as a whole.

RECLAIM CAMISSA's concerns with regard to the Water are focused on the need to protect and conserve the resource for future use by the public. For this purpose, the site requires investigation and evaluation in terms of the broader hydrological system, so that minimum setback distances around the groundwater resource together with development guideline standards to be established, that will offer basic protection for the resource.

The OCMA is integral to an internationally significant ecological and cultural system, to illustrate this, we provide the following rationale:

In terms of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NERA), the Stadtsfontein would have had continued protection, but it has been demoted from National Heritage Status.

On 4 October 2006, an application was made by the Oranjezicht Heritage Society to Heritage Western Cape with regard to a lease application for a portion on Erf no. 858, which was then a disused bowling green, upon which the Oranjezicht homestead once stood. The application included a motivation to have the land parcels (individual erven) consolidated into one single erf, so that a unified set of conservation guidelines could be applied for the sensitive treatment of the site.

The groundwater is integral to the site...

"Although the ultimate and comprehensive protection may not be a realistic goal, the concept of differentiated aquifer protection seems to indicate a more feasible option in achieving adequate protection qualitatively around different aquifer systems based on their classifications. This concept works on the premise that different aquifers due to their unique socio, economic and environmental importance require different levels of protection (Parsons and Conrad 1998). This protection may range from a simple generic setback distance (often referred to a minimum safe distance) around a water resource to a more complex mechanism of zoning. Source protection zoning seeks primarily to control land use activities, thus preventing or controlling pollution of groundwater resources. The method takes into account the concept of travel times and minimum safe distances to water supply and ensures that the time taken for the horizontal travel of the contaminant is sufficient to allow physical and biochemical degradation/dilution of the contaminant (DWAF 2008). The attenuation or elimination capacity of the sub-surface may in some cases reduce or completely eliminate the concentration of these contaminants via natural physical, chemical or biological processes.” -Yasmin Rajkumar and Yongxin Xu (2011)

Land use change on portion of Erf no. 858 (the former bowling green)

When the gardening lease from the CoCT was awarded to the Oranjezicht City Farm (OZCF), there was no Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, which should have been triggered by a change of land use in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NERA) and the Environment Conservation Act 73 0f 1989. In the development of the OCMP, it appears that the current land use (agriculture) has become acceptable. Whilst RECLAIM CAMISSA strongly support the concept of urban agriculture; and we commend the OZCF for having created a flourishing farm, and a powerful means by which to build community; and for making good use of previously fallow land - agriculture is not appropriate on the current land (portion of Erf No. 858). It is illegal in terms of both the The National Water Act, 1998 (NWA) and the National Environmental Management Act, 1998 (NEMA) to allow agriculture - a pollutant of water, over a major water source.

The current OZCF project has destroyed artefacts of heritage significance without approval from heritage agencies. (e.g. The rocks lining the old watersloot have been removed and sloot is now planted with tress). And although we focus our concerns on the water issues with regard to the protection and conservation of the site; at some later stage would like to engage directly with other stakeholders and/or institutions with regard to the establishment of an inventory of other items on site; and research material that would contribute to more fully inclusive narrative of the farm.

QUANTITY & QUALITY

Flow data collected in late February, 2013 reflects that four springs collecting within the field, issue an average of 5,987,520 litres of Water per day in late Summer. A limited quantity of this Water is utilised at the Green Point Eco Park, the balance flows out to sea - wasted through the tunnels under the city's streets.

Water economics specific to the Field of Springs

As a case study, Reclaim Camissa’s PGWC110%GREEN Flagship Project: “The Field of Springs” proposed the capture and use of 6million litres of groundwater / day. The intent for the project, was to:

- secure the water from 5 springs that collect in the Field of Springs;

- secure potable water through utilising natural filtration methods and a wetland system of retention and detention ponds, with the re-introduction of natural bio-diversity (plant & animal) to the eco-system; and incorporating bio-mimicry.

- secure non-potable water for re-use in the city’s green open spaces (fields, parks, etc); street trees; urban landscaping; urban farming; and fountains.

- create awareness of our local natural and cultural heritage, by providing experiential public education and recreational use of the site.

- provide appropriate public infrastructure (board walks; platforms and public furniture) thus protecting the water whilst enabling visitors to enjoy the site via ‘controlled’ means - allowing for the site to be the public asset that it should be.

- foster environmental education through various demonstration models, including local small-scale hydro-power for energy requirements and utilities on site.

- provide an open air public environmental education space that show cases the city’s natural and cultural heritage around water – through the provision of information and signage; and experimental demonstration models; and an outdoor water testing laboratory.

- provide blue economy enterprise opportunities and jobs.

At a quantum level - the project sets the precedent, whereby similar projects could be rolled out in other areas of the GCTMA.

The benefits of reclaiming and processing this water:

By capturing potable Water at source for domestic and or commercial use the city would be enabled to embark on a project that satisfies Water needs, geographically closer to source. The resultant reduction in infrastructural expansion; maintenance and simultaneous reduction in loss of non-revenue Water (nationally 38.6%); the savings in energy to pump the equivalent quantity of Water from the Overberg; and disaster risk management strategies necessitated by Water catchment management areas that are geographically remote from the point of consumption - would translate into a reduced treatment and supply cost per kl compared with conventional current water supply strategies.

It is envisaged that once the water from the 5 springs in the Field of Springs is captured, and processed for use as part of the city’s potable Water supply, revenue generated through the sale of the Water would provide a (self-sustaining) financial opportunity to reclaim and develop future Water conservation precinct areas that are integral to the hydrological system; and for the management and operation of the system as a whole. In addition, a small portion of this Water sold via a green economy enterprise, such as a bicycle brigade to distribute Water for offices and restaurants; that free spring Water drinking fountains as way finders and public artworks, would display the city's Water, past and future - throughout the CBD.

The direct benefits from reclaiming and processing 4million litres/day - thereby retaining 2million litres/day for the ecological reserve, translates to:

1. *R8.5m or *R16.6m per annum revenue income, using the lowest residential water pricing tariff of *R5.85 per kl or *R11.42 per kl for commercial and industrial usage, as published in the City's Integrated Development Plan. (*as calculated in 2014)

2. The Water captured at this site equates to the free basic Water supply (as prior to restrictions) of 20,277 homes, without impact on the Water resources, as this is Water not currently captured. As such the project benefits the wider Cape Town community notwithstanding its geographic positioning within an affluent suburb and reduces demand and supply pressure. It should be noted that on 8 November 2017, the CoCT published the augmentation of 2million litres of Water / day, to Molteno Reservoir - as calculated in 2014.

3. Due to the elevation at which these springs issue, the Water/Energy nexus potential, with 4.5KW measured on Erf. 861, could result in the power needs required by the study area, to be produced on site via local, small scale hydro-power.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Any authentically sustainable approach to Water use, planning, design and management needs to be adapted on acknowledgement of the intrinsic value of Water as a public resource that is not separate from the value of land and landscape.

The unprecedented urban growth rate represents an unique opportunity to build a more innovative, resource efficient and equitable Cape Town. In order to do so, a change in thinking about urbanization is necessary. For one, a paradigm shift is required at the system-wide level so that a framework for interventions over the entire Water cycle can be applied, which reconsider the way Water is used and reused throughout the urban context; and to take advantage of the opportunities for ecological services (i.e. “free services” provided by nature) as value added assets.

As examples:

A considerable asset to the central city, is the provision of renewable (clean) energy through interventions with the likes of Water wheels, turbines and new technologies, to provide for the lighting and other electrical services of the city's public spaces.

The unprecedented urban growth rate represents an unique opportunity to build a more innovative, resource efficient and equitable Cape Town. In order to do so, a change in thinking about urbanization is necessary. For one, a paradigm shift is required at the system-wide level so that a framework for interventions over the entire Water cycle can be applied, which reconsider the way Water is used and reused throughout the urban context; and to take advantage of the opportunities for ecological services (i.e. “free services” provided by nature) as value added assets.

As examples:

- Five of the springs, was a substantial supply. In the year 1896-1897, 811 000 000 imperial gallons of Water (364 950 000 litres) were run off. The elevation at which the Water was stored, made it very valuable for hydraulic power. Thomas Stewart in 1897, recorded that an effective 750 horse power was obtained for every 12 hours of every day, throughout the whole year.

- Graaff's Hydro-Electric, supplied Cape Town with electricity for street lights, whilst most of London still operated gas lamps, in 1895. See also here and here.

A considerable asset to the central city, is the provision of renewable (clean) energy through interventions with the likes of Water wheels, turbines and new technologies, to provide for the lighting and other electrical services of the city's public spaces.

The following recommendations are based on premises that the protection and conservation of ‘the commons’ is for all South Africans; and that manageable, incremental planning that works to address immediate needs also requires balancing how these measures fit into a broader framework of Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD) for the sustainable development of Cape Town.

These recommendations consider two key questions:

- What is the regulatory and governance body and regime for the management and operation of the hydrolo-spatial system?

- What needs to occur in order to protect and conserve the substantial Water resources issuing in the Field of Springs; and protect and conserve the hydrological system for optimal future utilisation?

SPRING PROTECTION ZONING

"Groundwater plays an increasingly important role as a source of potable Water - as such, it requires protection/conservation. The implementation of minimum setback distances around groundwater resources together with development guideline standards, would offer basic protection/conservation of the resource." -- Yasmin Rajkumar and Yongxin Xu in "Protection of borehole water quality in sub-Saharan Africa using minimum safe distances and zonal protection", Water Resource Management, Volume 23 No 4, March 2011, ISSN 0920-4741, Springer

Spring protection zoning, land-use management and development guideline standards are strongly advised in order to conserve and make optimal use of this valuable water resource, within the study area and it’s broader system.

It is a basic proposition of these recommendations, that the system is for the benefit of those around it, residents and their visitors as well as the general public, citizens and visitors to Cape Town, present and future. It is therefore recommended that system be contained; and managed as a contained system for and on behalf of all stakeholders, including the general public represented by the City of Cape Town (CoCT), the local residents - by the City Bowl Residents Association (CIBRA), and specialist civil society and technical experts.

In accordance with the The National Water Act, 1998 - appropriate intuitional arrangement is required to ensure the necessary governance is in place to protect, conserve and manage a water resource, in terms of the hydrological system and its ecological functioning.

The governance arrangements are to set out an agreed policy and implementing procedure, on behalf of all interest groups, which must include monitoring of the necessary protection and conservation measures. It is to manage, maintain and operate the water resource and the surrounding land, as well as add value to its betterment and use in the common interest.

It is necessary that an investigation be undertaken to analyse strategic scenarios informed by the environmental, political, economic and pragmatic realities in order to develop guidelines for the optimal use of both land and Water resources available in the study area - as integral to the system.

The first task therefore, is to undertake an investigation to design and implement the necessary governance arrangements, including institutional and management arrangements based on the spatio-hydrological system.

Protection of the hydrological system and its improvement - in order for it to render the maximum benefit to its users; as well as its on-going monitoring, operation and maintenance requires planning and finances. Thus, to define the project scope the investigation requires demarcating, measurement and evaluation of the 32 springs in the local area - to include flow dynamics, both quantitative and qualitative.

By regarding the resource as a flux, an economic impact analysis in conjunction with the selection of appropriate techniques and models to conserve, renew and utilise the resource - wherever pragmatically possible, is required. Thus synthesised, land use management guidelines can be derived to ensure measureable outcomes aligned with future project goals that would, ultimately protect the future availability and use of the Water resource and its hydrological system functioning. And such a governance structure could be applied to any of the other Water systems in the GCTMA.

"Groundwater plays an increasingly important role as a source of potable Water - as such, it requires protection/conservation. The implementation of minimum setback distances around groundwater resources together with development guideline standards, would offer basic protection/conservation of the resource." -- Yasmin Rajkumar and Yongxin Xu in "Protection of borehole water quality in sub-Saharan Africa using minimum safe distances and zonal protection", Water Resource Management, Volume 23 No 4, March 2011, ISSN 0920-4741, Springer

Spring protection zoning, land-use management and development guideline standards are strongly advised in order to conserve and make optimal use of this valuable water resource, within the study area and it’s broader system.

It is a basic proposition of these recommendations, that the system is for the benefit of those around it, residents and their visitors as well as the general public, citizens and visitors to Cape Town, present and future. It is therefore recommended that system be contained; and managed as a contained system for and on behalf of all stakeholders, including the general public represented by the City of Cape Town (CoCT), the local residents - by the City Bowl Residents Association (CIBRA), and specialist civil society and technical experts.

In accordance with the The National Water Act, 1998 - appropriate intuitional arrangement is required to ensure the necessary governance is in place to protect, conserve and manage a water resource, in terms of the hydrological system and its ecological functioning.

The governance arrangements are to set out an agreed policy and implementing procedure, on behalf of all interest groups, which must include monitoring of the necessary protection and conservation measures. It is to manage, maintain and operate the water resource and the surrounding land, as well as add value to its betterment and use in the common interest.

It is necessary that an investigation be undertaken to analyse strategic scenarios informed by the environmental, political, economic and pragmatic realities in order to develop guidelines for the optimal use of both land and Water resources available in the study area - as integral to the system.

The first task therefore, is to undertake an investigation to design and implement the necessary governance arrangements, including institutional and management arrangements based on the spatio-hydrological system.

Protection of the hydrological system and its improvement - in order for it to render the maximum benefit to its users; as well as its on-going monitoring, operation and maintenance requires planning and finances. Thus, to define the project scope the investigation requires demarcating, measurement and evaluation of the 32 springs in the local area - to include flow dynamics, both quantitative and qualitative.

By regarding the resource as a flux, an economic impact analysis in conjunction with the selection of appropriate techniques and models to conserve, renew and utilise the resource - wherever pragmatically possible, is required. Thus synthesised, land use management guidelines can be derived to ensure measureable outcomes aligned with future project goals that would, ultimately protect the future availability and use of the Water resource and its hydrological system functioning. And such a governance structure could be applied to any of the other Water systems in the GCTMA.

A comprehensive study requires to be undertaken which, simply put -

- demarcates the spatial and hydrological limits / parameters of the system;

- establishes the resources reference conditions, resources management classes and resources quality objectives;

- determines resource directed measures for the Oranjezicht Conservation Management Plan (OCMP) based on The National Water Act, 1998 and sets out the legal or best practice measures for land use and hydrological/environmental restrictions for its protection; and

- builds a ‘business model’ for its utilisation and the utilisation of the land - in the case of the study area: The Field of Springs - to generate the revenues for its on-going management, maintenance and operation.

It is with thanks to the guidance of UNESCO's Groundwater Chair, Prof. Yongxin Xu and Reclaim Camissa Board Members, Ms. Kiki Bond-Smith and Ms. Caron von Zeil, for their respective expertise in assisting Reclaim Camissa's response to the CoCT regarding the necessity to protect the Field of Springs. It is hoped, that the concerns and recommendations made on behalf of RECLAIM CAMISSA will contribute to the conservation of the city’s Water resources, and that the CoCT revisits their Water security strategy and undertakes a comprehensive study and evaluation - as has been recommended.

REFERENCES & OTHER SOURCES OF INFORMATION

- GLOBAL WATER PARTNERSHIP: Water Statistics

- Global Water Partnership: New Global Strategy Towards 2020 (Press Release)

- International Water Management Institute (IWMI)

- David Dodman, Gordon McGranahan and Barry Dalal-Clayton: "The Environment in Urban Planning and Management - Key Principles and Approaches for Cities in the 21st Century", International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED).

- Ben Braga: "Enhancing water security in urban areas", 2018.

- Integrating the Environment In Urban Planning And Management - UNEP, 2016.

- UN-Habitat: Guiding principles for city climate action planning 1, 2015.

- CoCT: Water Services Development Plan, WSDP 2012-2013.

- Global Water Partnership: "Water and Urbanisation", 2013.

- UN-Water Analytical Brief on Water Security and the Global Water Agenda, 2013.

- Karen Bakker: "Water Security: Research Challenges and Opportunities" in Science, vol.337 no. 6097, 2012.

- Bloch, Robin; Jacobsen, Michael; Webster, Michael; Vairavamoorthy, Kalanithy: "The future of water in African cities - why waste water?" Integrating urban planning and water management in Sub-Saharan Africa (background report), World Bank, 2012.

- Yasmin Rajkumar and Yongxin Xu: “Protection of borehole water quality in sub-Saharan Africa using minimum safe distances and zonal protection”, Water Resource Manage, Volume 23 No 4, March 2011, ISSN0920-4741, Springer, 2011.

- The NYC Green-frastructure Plans

- National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NERA).

- Jan Lundqvist: "Avert Looming Hydrocide" - Volume 12 of Publications on water resources, ISSN 1401-4300, 1998.

- The National Water Act, 1998.

- The National Environmental Management Act, 1998.

- Pierre Frühling: "A liquid more valuable than gold - the water crisis in southern Africa, future risks and solutions", SIDA,1996.

- Xu, Y. & Braune, E.: "A guideline for groundwater protection for the community water supply and sanitation programme", Published by the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, RSA, ISBN: 0-621-16787-8, 1995.

- CoCT Brochure: Cape Town Electricity 1895 - 1995: 100 years at your service, 1995.

- The Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989.

- Engineers Report: Augmentation of water supply 1923, Steenbras Scheme,1923.

- Thomas Stewart: "Additional Storage Reservoir on Table Mountain", 1897.

- Pritchard, E: Cape Town Sewerage, 1889.

ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED by THE RECLAIM CAMISSA TRUST No. IT 2882/2010.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.

This is a citizen-scientist open source database. By acknowledging and referencing the source, you are welcome to use the material and information provided here for the common good.

All research, spatial framework and proposals are the intellectual property of Caron von Zeil.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed